Enzo Ferrari – Der Mann, der den Mythos erschuf Teil 2 von 4:

Kapitel 4: Der Bruch mit Alfa Romeo und der erste „echte“ Ferrari

Der Bruch mit Alfa Romeo war keine spontane Entscheidung. Er war das Ergebnis eines jahrelangen Spannungsfelds aus Macht, Stolz und Kontrolle. Für Enzo Ferrari, der sich nie als einfacher Angestellter, sondern stets als Taktgeber verstand, wurde es zur unausweichlichen Konsequenz: Er musste sich von Alfa lösen, um Ferrari zu schaffen – nicht nur als Team, sondern als eigenständige Automobilmarke.

4.1 Ein Konflikt mit Geschichte – Rivalität unter Freunden

Die Verbindung zwischen Enzo Ferrari und Alfa Romeo war nie nur eine berufliche. Sie war Beziehung, Partnerschaft, Duell und schließlich Trennung mit Nachbeben. Es war eine dieser komplexen Verbindungen, wie man sie aus großen Biografien kennt: geprägt von gegenseitigem Respekt, doch unterfüttert mit Konkurrenz, Stolz und tiefen ideologischen Unterschieden. Die Rivalität, die sich zwischen Enzo Ferrari und den Entscheidungsträgern bei Alfa Romeo entwickelte, war nicht abrupt. Sie war das Ergebnis eines über Jahre gärenden Spannungsfeldes – und mündete letztlich in einer der bedeutendsten Entscheidungen der Automobilgeschichte.

Die frühen Jahre – Ferrari wird zum Alfa-Mann

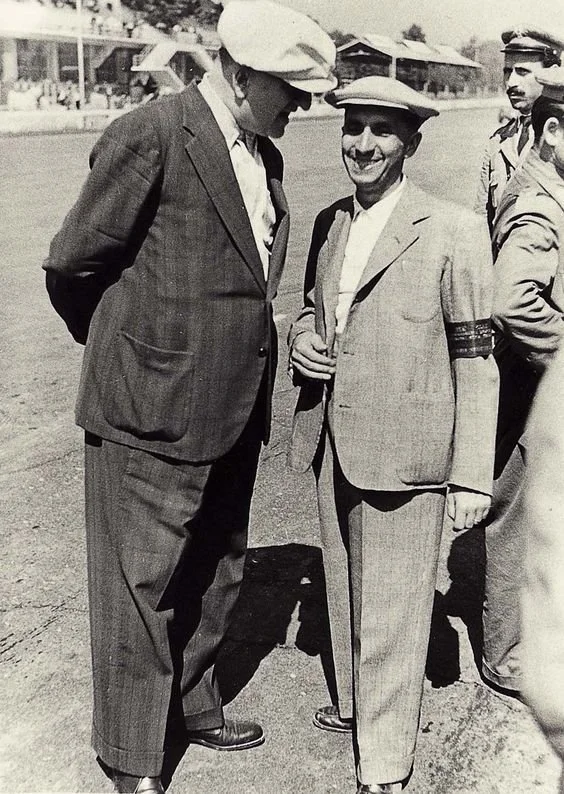

Als Enzo Ferrari Anfang der 1920er bei Alfa Romeo als Fahrer einstieg, war er kein gefeierter Rennheld. Er war talentiert, ja, aber nicht brillant. Was ihn unterschied, war sein Blick für das große Ganze: Ferrari interessierte sich für die Technik, die Organisation, die Strategie hinter dem Erfolg. Schon bald wurde Alfa klar, dass dieser junge Mann mit scharfem Verstand und organisatorischem Instinkt weit mehr als nur ein Lenkrad bedienen konnte.

Ab Mitte der 1920er wurde Enzo zu einer der treibenden Kräfte hinter Alfas Rennsportstrategie. Nach außen hin trat er als Fahrer auf, hinter den Kulissen agierte er jedoch bereits als Strippenzieher, als Talentsucher, als Taktiker. Während andere Fahrer zwischen Rennen und Werkstatt pendelten, baute Enzo ein Netzwerk auf – zu Mechanikern, Sponsoren, Lokalpolitikern und Journalisten. Er war dabei, sich seinen eigenen Einflussbereich zu schaffen – innerhalb eines Unternehmens, das stolz auf seine Strukturen und Traditionen war.

Die Gründung der Scuderia – Eigenständig im Schatten von Alfa

1929 gründete Enzo Ferrari in Modena die Scuderia Ferrari – offiziell eine private Organisation zur Betreuung von Gentleman-Fahrern, inoffiziell jedoch bald das Quasi-Werksteam von Alfa Romeo. Ferrari bereitete Fahrzeuge vor, stellte Fahrer unter Vertrag, organisierte Rennlogistik und betreute bis zu 40 Autos gleichzeitig – eine gewaltige Leistung.

Alfa Romeo, wirtschaftlich angeschlagen durch die Nachwirkungen der Weltwirtschaftskrise, war zu diesem Zeitpunkt nur allzu bereit, den aufwändigen Rennbetrieb auszulagern. Die Scuderia Ferrari übernahm diese Rolle mit Begeisterung – und Erfolg. Zwischen 1930 und 1937 erzielten Ferrari und seine Mannschaft unzählige Siege für Alfa: Mille Miglia, Targa Florio, Grand Prix von Italien. Namen wie Tazio Nuvolari, Giuseppe Campari oder Achille Varzi prägten diese goldene Ära.

Doch dieser Erfolg hatte einen Preis: Die Aufmerksamkeit verschob sich. Immer öfter wurde Enzo Ferrari selbst zur Hauptfigur in den Medien – nicht Alfa Romeo. Das springende Pferd begann, den Schriftzug „Alfa“ zu überschatten.

Zwei Führungsstile prallen aufeinander

Alfa Romeo war ein Konzern – geprägt von Ingenieuren, Technokraten, Verwaltungsorganen. Ferrari hingegen war ein charismatischer Alleinherrscher, jemand, der lieber entschied als diskutierte, der auf sein Bauchgefühl vertraute, nicht auf Komitees.

Während Alfa Romeo auf formale Prozesse setzte, bevorzugte Ferrari die intuitive Führung: Er ließ Fahrer gegeneinander antreten, um das Beste aus ihnen herauszuholen. Er zwang seine Mechaniker zu Nachtschichten, wenn er das Gefühl hatte, ein Wagen sei nicht optimal vorbereitet. Und er stellte immer wieder Quereinsteiger ein, denen er mehr Talent als Ausbildung zutraute.

Diese Differenzen waren zunächst Reibung, später Rebellion. Ferrari hasste es, „Briefe nach Mailand zu schreiben, um Entscheidungen zu bekommen, die er längst getroffen hatte.“ Alfa wiederum sah mit wachsendem Argwohn, wie sich Enzo ein eigenes „Königreich“ in Modena schuf.

„Ich war nie gegen Alfa. Aber ich war gegen ihre Denkweise.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Am 6. September 1939 verließ Enzo Ferrari offiziell Alfa Romeo. Doch der Abschied hatte seinen Preis: Als Teil der Vereinbarung musste Ferrari eine heikle Klausel unterschreiben – sie verbot ihm für die Dauer von vier Jahren, Fahrzeuge unter dem Namen „Ferrari“ zu produzieren oder zu verkaufen.

Was wie eine juristische Formalie wirkte, war für Enzo ein Tiefschlag gegen seinen Stolz. Sein Name war seine Marke – und genau diese sollte er nicht nutzen dürfen. Doch statt zu kapitulieren, reagierte Ferrari wie so oft in seiner Karriere: mit List, mit Geduld – und mit Planung.

1937: Die Übernahme – Beginn vom Ende

Im Jahr 1937 eskalierte die Situation. Alfa Romeo entschloss sich, den Motorsport wieder direkt ins Unternehmen zurückzuholen. Die Scuderia Ferrari sollte eingegliedert werden, Enzo Ferrari als Sportdirektor in eine Position ohne Entscheidungsgewalt gesetzt werden. Für Enzo war das ein Affront. Er sah sich nicht als Angestellten, sondern als Schöpfer, als Gestalter des Erfolgs.

Die Entscheidung, ihn in die zweite Reihe zu verbannen, war vielleicht der größte strategische Fehler Alfas. Enzo akzeptierte die neue Rolle widerwillig, doch intern begann er, sich abzukoppeln. Er erkannte, dass er unter diesen Bedingungen nicht mehr agieren konnte – und dass seine Vision eines echten Automobilherstellers nie unter der Alfa-Flagge verwirklicht werden würde.

Der unterschwellige Krieg – Misstrauen auf beiden Seiten

Zwischen 1937 und 1939 herrschte ein unterschwelliger Machtkampf. Enzo wurde von Alfa immer stärker reglementiert, seine Kontakte beschnitten, seine Handlungsspielräume verkleinert. Gleichzeitig spürte Alfa, dass Ferrari begann, eigene Strukturen aufzubauen – er stellte Mitarbeiter abseits der offiziellen Wege ein, experimentierte heimlich mit Konstruktionen, sondierte Lieferanten.

Insider berichten, dass Ferrari bereits 1938 in Kontakt mit dem Ingenieur Gioachino Colombo stand, um eine neue V12-Motorarchitektur zu besprechen – ein Antrieb, der nichts mit Alfas damaligen Plänen zu tun hatte. Es war klar: Der Bruch war nur noch eine Frage der Zeit.

Der Abschied – Mehr als ein formeller Schritt

Im September 1939 – kurz vor dem Beginn des Zweiten Weltkriegs – zog Ferrari die Konsequenz. Er verließ Alfa Romeo. Der offizielle Grund war „Neustrukturierung“, inoffiziell war es ein klarer Akt der Rebellion. Doch Alfa ließ ihn nicht ungeschoren davonziehen. Eine Klausel im Trennungsvertrag untersagte es Enzo Ferrari, für die Dauer von vier Jahren den Namen „Ferrari“ im Automobilbereich zu nutzen.

Es war ein Schlag unter die Gürtellinie. Für jemanden, der sein gesamtes Schaffen unter seinem Namen sah, war das eine persönliche Demütigung. Doch Enzo nahm die Herausforderung an. Und wie so oft, war er bereits einen Schritt voraus: Die Firma Auto Avio Costruzioni war schon gegründet. Der Umzug nach Maranello war bereits geplant. Das nächste Kapitel konnte beginnen.

„Man kann mir meinen Namen nehmen. Aber nicht meine Ideen.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Eine Rivalität, die Legenden schuf

Die Rivalität zwischen Enzo Ferrari und Alfa Romeo war keine Feindschaft im klassischen Sinne. Sie war eine Trennung aus Prinzipien, aus Stolz, aus tiefen Differenzen in der Philosophie. Ohne Alfa hätte Enzo nie die Bühne bekommen, um sein Talent zu entwickeln. Aber ohne den Bruch hätte es Ferrari als Marke nie gegeben.

Diese Konfliktgeschichte zeigt, wie große Ideen oft aus Spannungen geboren werden. Und dass wahre Größe nicht im Gehorsam liegt – sondern im Mut, eigene Wege zu gehen.

4.2 Der Pakt mit dem Teufel: Vertragsklausel gegen den eigenen Namen

Als Enzo Ferrari im Herbst 1939 Alfa Romeo endgültig verließ, war es kein triumphaler Abgang mit wehenden Fahnen. Es war ein leiser, kalter Rückzug – begleitet von juristischen Fesseln, die ihm tiefer ins Fleisch schnitten als jede wirtschaftliche Bürde. Denn bei der Trennung stimmte Enzo einem Passus zu, der ihn über Jahre hinweg in seiner größten Ambition behindern sollte: Er durfte keine Autos unter seinem eigenen Namen bauen.

Ein taktisches Bauernopfer

Die Vertragsklausel war keine Nebensächlichkeit. Sie war das Ergebnis zäher Verhandlungen zwischen dem Alfa-Management und Enzo, der – trotz seines Stolzes – wusste, dass er keine Verhandlungsstärke mehr hatte. Alfa Romeo wollte verhindern, dass Ferrari nach dem Bruch sofort eine Konkurrenzmarke aufbaut. Besonders fürchtete man den Abfluss von Fahrern, Mechanikern und Kunden – also genau jenen Netzwerken, die Enzo über Jahre kultiviert hatte.

Ferrari war sich der Brisanz bewusst. Doch in einer Zeit, in der sich Europa bereits im Krieg befand, war nicht die Stunde für offene Konflikte. Enzo unterschrieb – zähneknirschend, aber mit einem klaren Plan im Kopf. Vier Jahre, so hieß es in der Vereinbarung, dürfe er kein Unternehmen führen, das unter dem Namen „Ferrari“ Fahrzeuge produziere oder vertreibe. Auch Werbung, Motorsportaktivitäten und technologische Entwicklungen mit dem Familiennamen waren untersagt.

„Ich habe meinen Namen verkauft, um meine Freiheit zu behalten.“

– Enzo Ferrari (später über diese Zeit)

Eine Identität ohne Namen

Für Enzo Ferrari war sein Name mehr als eine Signatur. Er war Marke, Anspruch, Erbe und Verpflichtung zugleich. Der Gedanke, vier Jahre lang ein Projekt aufzubauen, das seinen Namen nicht tragen durfte, widersprach allem, woran er glaubte. Und doch nutzte er genau diese Einschränkung als kreativen Brennstoff.

Ferrari war noch nicht Ferrari – aber Enzo war schon Enzo. Seine Reputation, sein Netzwerk und seine Vision machten ihn bereits zur lebenden Marke. Er musste nur Wege finden, diese Marke ohne Worte sichtbar zu machen.

Auto Avio Costruzioni – Das trojanische Pferd

Nur wenige Wochen nach dem offiziellen Bruch gründete Enzo Ferrari im Dezember 1939 die Firma Auto Avio Costruzioni (AAC) mit Sitz in Modena. Auf dem Papier stellte das Unternehmen mechanische Komponenten her, darunter Fräsmaschinen, Werkzeugteile und Komponenten für die Luftfahrt – Produkte, die kriegsbedingt gefragt waren.

Doch der wahre Zweck der Firma lag tiefer: AAC war das trojanische Pferd, mit dem Enzo Ferrari seine Ideen unter Umgehung der Namensklausel weiterverfolgte. Bereits Anfang 1940 begann er – unter strengster Geheimhaltung – mit der Entwicklung eines Sportwagens, der zwar nicht „Ferrari“ heißen durfte, aber alles in sich trug, was später zur DNA der Marke werden sollte.

Das Projekt: der Tipo 815.

Der Typ 815 – Mehr als ein Experiment

Mit dem Tipo 815 präsentierte Enzo 1940 das erste Fahrzeug aus eigenem Haus – mit einem 1,5-Liter-Reihenachtzylindermotor und einer filigranen Karosserie von Touring Superleggera. Nur zwei Exemplare wurden gebaut, beide für die Teilnahme an der Mille Miglia vorgesehen. Offiziell wurde das Fahrzeug als AAC Tipo 815 gemeldet, inoffiziell wussten alle Beteiligten: Dies war der erste echte Ferrari.

Dass beide Wagen das Rennen nicht beendeten, tat der Symbolik keinen Abbruch. Der 815 war kein Erfolgsmodell, aber ein Manifest. Ein Versprechen. Eine Botschaft an die Welt: Ferrari ist nicht verschwunden – Ferrari wartet.

Die Klausel als Katalysator

Rückblickend war die Namensklausel weniger ein Hindernis als ein Katalysator für Ferraris Kreativität. Sie zwang ihn, Wege zu finden, sich durch Qualität, Charakter und persönliche Netzwerke durchzusetzen – nicht durch Markenpower. Diese Erfahrung prägte seine spätere Unternehmensphilosophie zutiefst: Nicht der Name verkauft Autos, sondern der Mythos dahinter.

Die vier Jahre gingen schneller vorbei, als man es erwarten konnte – auch, weil der Zweite Weltkrieg die Prioritäten verschob. Als der Krieg endete und die Klausel 1943 auslief, war Enzo bereit. Er hatte Personal, Know-how, eine Werkstatt – und eine Vision. Alles, was noch fehlte, war ein Auto mit seinem Namen darauf.

Und das kam 1947.

4.3 Auto Avio Costruzioni – Das trojanische Pferd

Der Mythos Ferrari wurde nicht auf offener Bühne geboren, sondern im Schatten, während Europa in Flammen stand und die Welt in Krieg und Chaos versank. Während große Konzerne ihre Kapazitäten auf die Rüstungsproduktion umstellten, legte Enzo Ferrari mit seinem neuen Unternehmen Auto Avio Costruzioni (AAC) den Grundstein für eine Zukunft, die erst nach 1945 ihren Namen tragen durfte. Für vier Jahre durfte „Ferrari“ nicht auf einem Auto stehen – aber das hinderte Enzo nicht daran, seinen Traum weiterzubauen. Heimlich, zielstrebig, unerbittlich.

Ein Deckmantel mit doppeltem Boden

Im Herbst 1939, unmittelbar nach dem formellen Bruch mit Alfa Romeo, gründete Enzo Ferrari Auto Avio Costruzioni – ein Unternehmen, das zunächst nichts mit Sportwagen zu tun hatte. Offiziell gab es keinen Motorsportbezug, keinen Entwicklungsauftrag für Fahrzeuge. Stattdessen wurde AAC als mechanische Werkstatt mit Spezialisierung auf Präzisionsteile ins Handelsregister eingetragen. Der Fokus: Werkzeuge, Maschinenkomponenten und – in späteren Kriegsjahren – Flugzeugteile.

Doch das war nur die eine Seite. Die andere, verborgene Seite war eine geheime Entwicklungszelle für zukünftige Rennsporttechnologie. Enzo nutzte sein verbliebenes Netzwerk aus der Scuderia Ferrari: alte Ingenieure, loyale Mechaniker, Vertrauensleute. Darunter Männer wie Luigi Bazzi, ein begnadeter Techniker, der bereits bei Alfa mit Enzo gearbeitet hatte, sowie Karosseriebauer Carrozzeria Touring, mit dem eine diskrete Kooperation entstand.

Was nach außen wie ein kleiner Zulieferbetrieb wirkte, war in Wahrheit ein trojanisches Pferd: eine Tarnfirma, in der unter Ausschluss der Öffentlichkeit bereits wieder Rennwagen gedacht, gezeichnet und montiert wurden – nur eben ohne das Wort „Ferrari“.

Das Projekt 815 – Technik unter dem Radar

Nur wenige Monate nach der Gründung wurde im Inneren von AAC ein Fahrzeug entwickelt, das später als der erste inoffizielle Ferrari gelten sollte: der Tipo 815. Der Name war ein nüchternes Kürzel – 8 Zylinder, 1.5 Liter Hubraum – doch unter der schlichten Bezeichnung steckte eine bedeutungsvolle Konstruktion.

Die Basis des Motors war eine Weiterentwicklung des Fiat 508C – eines Massenfahrzeugs –, doch Ferrari und seine Ingenieure bauten ihn von Grund auf um: Zwei 4-Zylinder-Blöcke wurden zu einem Reihenachtzylinder kombiniert. Der Motor leistete etwa 72 PS bei 5500 U/min – beeindruckend für die damalige Zeit in dieser Klasse.

Noch wichtiger war das Ziel: Teilnahme an der legendären Mille Miglia 1940. Trotz der nahenden Kriegsereignisse wurde das Rennen noch einmal ausgetragen, allerdings in verkürzter Form (Brescia–Cremona–Mantua–Brescia, ca. 1500 km). Zwei Tipo 815 wurden gebaut. Einer davon fuhr der junge, talentierte Alberto Ascari, der spätere zweifache Formel-1-Weltmeister.

Beide Fahrzeuge fielen aus – technische Probleme, unzureichende Vorbereitung. Doch das war zweitrangig. Für Enzo Ferrari war dieses Rennen ein symbolischer Akt: Er war zurück im Rennen. Nicht öffentlich, nicht unter eigenem Namen – aber zurück.

„Der 815 war ein flüsternder Schrei. Kein Publikum, kein Applaus – nur der Motor und der Wille, weiterzumachen.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Kriegsjahre und Verlagerung nach Maranello

Kurz nach dem Rennen wurde klar: Die Lage in Europa ließ keine weiteren Motorsportaktivitäten zu. Die Werkstatt in Modena wurde mehr und mehr in die Herstellung kriegsrelevanter Bauteile eingebunden – eine Zwangsanpassung, die Ferrari geschickt nutzte, um Zulieferverträge zu sichern und Kapital aufzubauen.

Doch Modena war nicht sicher. 1943, als die Luftangriffe auf Norditalien zunahmen, entschied Enzo, den Betrieb nach Maranello zu verlegen – ein unscheinbares Dorf etwa 18 Kilometer südlich. Dort begann er mit dem Bau einer neuen Produktionsstätte – vorgeblich für Lagertechnik und Präzisionsteile, tatsächlich aber für eine Zukunft, die bereits auf dem Reißbrett lag.

Diese Verlagerung war ein Meisterstück strategischer Weitsicht. Während ganz Italien unterging, schuf Ferrari seine eigene Festung, fernab der politischen Zentren, mitten im Grünen – und legte damit das Fundament für das, was heute noch der Stammsitz von Ferrari ist.

Was bleibt vom AAC-Kapitel?

Die Auto Avio Costruzioni war eine Episode im Ferrari-Mythos, die oft unterschätzt wird – dabei war sie von essenzieller Bedeutung. Ohne AAC hätte es keine organisatorische Kontinuität gegeben, keinen Motorenversuch, keine Weiterentwicklung technischer Konzepte. Enzo Ferrari überstand den Krieg nicht nur wirtschaftlich, sondern organisatorisch gestärkt.

Als 1947 die berühmte Vertragsklausel auslief, musste er nicht bei null anfangen – er hatte bereits ein Team, ein Werk, ein Testgelände, Lieferanten und Know-how. Er musste nur noch tun, was er seit acht Jahren geplant hatte: den Namen „Ferrari“ auf ein Auto schreiben.

4.4 Der Krieg als Brandbeschleuniger

Der Zweite Weltkrieg war für Europa eine Zeit der Verwüstung, des Stillstands und der Angst. Für Enzo Ferrari jedoch wurde diese düstere Epoche – bei aller menschlichen und wirtschaftlichen Härte – auch zu einem unfreiwilligen Katalysator. Der Krieg bremste seine Ambitionen als Automobilbauer kurzfristig aus, zwang ihn zu Improvisation und Anpassung – aber genau dadurch schärfte er seinen unternehmerischen Instinkt, sammelte Ressourcen und bereitete im Verborgenen den größten Neustart seines Lebens vor.

Die politischen Umstände – ein Tanz auf dem Drahtseil

Nach der Gründung von Auto Avio Costruzioni 1939 und dem Projekt Tipo 815 im Jahr 1940 verschob sich die politische Lage rasant. Italien trat aktiv in den Krieg ein, Mussolinis faschistisches Regime stellte die Industrie zunehmend unter staatliche Kontrolle. Ferrari, der nie politisch war, musste sich zwischen Loyalität und Überleben entscheiden.

Er entschied sich für taktisches Kalkül: Statt Widerstand zu leisten oder in die Isolation zu gehen, passte er sich äußerlich an – und stellte die Produktion auf kriegsrelevante Komponenten um. Seine Firma lieferte Teile für Flugzeugmotoren, Präzisionsfräsen, mechanische Steuerungselemente. Keine eigenen Autos, kein Motorsport – zumindest nicht offiziell.

Diese Phase war keine Zeit des Glanzes, aber sie war eine Zeit des Wachstums im Schatten. Ferrari baute Netzwerke zu staatlichen Stellen auf, sicherte sich Materialien und Maschinen – und lernte, wie man ein Unternehmen unter maximalem Druck am Leben hält.

1943: Der Umzug nach Maranello – Zuflucht und Strategie

Ein Schlüsselmoment in dieser Phase war der Entschluss, die Werkstatt in Modena zu verlassen. Die zunehmenden Luftangriffe, die Nähe zu wichtigen Bahnverbindungen und Fabriken machten die Stadt gefährlich. Enzo entschied sich, in das abgelegene, bäuerlich geprägte Maranello umzuziehen – ein Ort, der weit genug vom militärischen Fokus entfernt lag, aber logistisch gut erreichbar blieb.

Dort errichtete er eine neue Fertigungsanlage, die offiziell der Herstellung von Maschinenteilen diente. Doch zwischen den Werkbänken und in den Konstruktionsbüros wurde bereits an einer Zukunft gedacht, die mit Präzisionsteilen nichts zu tun hatte. Maranello wurde zur Keimzelle des Mythos – ein Ort, an dem Technik, Ehrgeiz und Isolation eine hochexplosive Mischung ergaben.

1944: Bomben und Wiederaufbau

Die vermeintliche Sicherheit Maranellos hielt nicht ewig. Am 27. November 1944 wurde Ferraris neue Fabrik durch einen alliierten Luftangriff fast vollständig zerstört. Das Gelände lag in der Nähe einer Bahnstrecke, was es auf die Liste möglicher Ziele brachte. Enzos gesamter Aufbau – Maschinen, Materialien, Pläne – ging in Flammen auf.

Für viele Unternehmer wäre das das Ende gewesen. Doch Ferrari reagierte anders. Er sah die Zerstörung nicht als Niederlage, sondern als Gelegenheit zur Optimierung. Noch während der Rauch aufzog, ließ er aufräumen. Er organisierte neue Geräte, holte sein altes Netzwerk zurück, reaktivierte Kontakte bei Zulieferern und Behörden. Seine Vision war ungebrochen.

„Wenn der Himmel mir das Dach nimmt, baue ich ein größeres.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Kriegsende: Startlinie neu gezogen

Als der Krieg 1945 endete, war Italien ein zerstörtes Land – wirtschaftlich am Boden, politisch gespalten. Doch in Maranello war das Gegenteil der Fall: Dort stand eine kleine, moderne Fabrik, bereit zur Nutzung, geführt von einem Mann, der in den schwierigsten Jahren nicht nur durchgehalten, sondern vorausgedacht hatte.

Die Vertragsklausel, die ihm bis 1943 die Verwendung seines Namens verboten hatte, war nun abgelaufen. Die Infrastruktur war vorhanden. Die Mannschaft stand bereit. Enzo Ferrari musste nichts mehr verstecken. Er konnte endlich tun, was er acht Jahre lang vorbereitet hatte:

Seinen Namen auf die Motorhaube schreiben.

Kapitel 5: Maranello wird zur Geburtsstätte des Mythos

Der Wiederaufbau in Maranello war kein Akt der Kapitulation, sondern ein Akt der Vision. Während große Teile Europas noch in Trümmern lagen, richtete Enzo Ferrari seinen Blick bereits wieder nach vorn. Dort, wo wenige Monate zuvor Bomben explodierten und das AAC-Werk zerstört worden war, sollte eine neue Ikone geboren werden. Es war nicht nur ein Wiederaufbau der Werkstatt – es war die Geburt eines Ortes, der zur geistigen Heimat einer weltweiten Bewegung werden sollte: Ferrari in Maranello.

5.1 Der neue Anfang in Maranello

Maranello im Jahr 1945. Der Krieg war vorbei, aber seine Spuren waren überall sichtbar: zerbombte Städte, zerstörte Infrastruktur, wirtschaftliche Verwüstung. Italien lag am Boden. Doch inmitten dieser Trümmerlandschaft stand ein Ort, an dem die Zukunft nicht in der Vergangenheit versank, sondern mit geradezu trotzigem Willen erschaffen wurde: Ferraris neue Werkstatt, ein unscheinbarer Gebäudekomplex, der bald zur Keimzelle einer der größten Marken der Automobilgeschichte werden sollte.

Für Enzo Ferrari bedeutete Maranello mehr als nur einen physischen Standort. Es war sein eigenes Reich, frei von Einflüssen, ohne Vorgesetzte, ohne Kompromisse. Er hatte das Unternehmen Auto Avio Costruzioni durch den Krieg manövriert, seine Produktionsanlagen neu aufgebaut und wartete nun nur noch auf den Moment, an dem er wieder das tun konnte, wofür er lebte: ein eigenes Auto bauen – unter seinem eigenen Namen.

Ein Ort wie kein anderer

Maranello war eine kluge Wahl. Das ländliche Dorf in der Provinz Modena bot vor allem eines: Ruhe. Keine großen Industriebetriebe, keine kriegswichtige Infrastruktur, keine politische Aufmerksamkeit. Gleichzeitig war es nicht zu weit von den gewohnten Verbindungen entfernt – Lieferanten, Ingenieure und potenzielle Kunden waren in Norditalien schnell erreichbar.

Doch vor allem bedeutete Maranello für Enzo Ferrari Kontrolle. Die Fabrik wurde nach seinen Vorstellungen errichtet – funktional, pragmatisch, aber durchdacht. Alles sollte effizient, technisch und diszipliniert ablaufen. Wer hier arbeitete, wusste: Dies war kein gewöhnlicher Arbeitsplatz, sondern ein Ort, an dem ein Mythos erschaffen wurde – und an dem der Anspruch an jedes Teil, jede Schraube, jedes Detail über dem Durchschnitt lag.

„Ich wollte keine Hallen bauen, ich wollte einen Geist erschaffen.“

– Enzo Ferrari

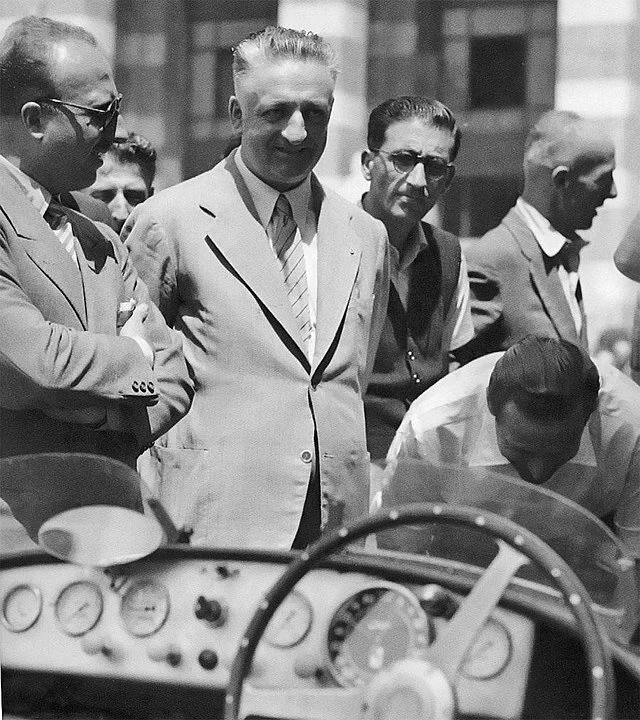

Die Menschen hinter dem Neuanfang

Enzo Ferrari wusste, dass Maschinen nur so gut sind wie die Menschen, die sie bedienen. Deshalb umgab er sich mit einem kleinen, aber extrem fähigen Team aus Ingenieuren, Technikern und alten Weggefährten. Viele davon hatte er schon zu Zeiten der Scuderia oder bei Auto Avio Costruzioni kennengelernt. Einige waren ehemalige Alfa-Leute, die – enttäuscht von der Entwicklung dort – in Ferrari einen visionären Anführer sahen.

Zentral war vor allem ein Name: Gioachino Colombo. Der brillante Motorenentwickler hatte bereits bei Alfa Romeo mit Enzo zusammengearbeitet und wurde nun beauftragt, einen Motor zu entwerfen, der nichts weniger sein sollte als die Essenz von Ferrari.

Colombo lieferte einen Entwurf für einen 1,5-Liter-V12-Motor – kompakt, leistungsstark, technisch innovativ. Ein V12 war für ein kleines Unternehmen eigentlich überdimensioniert – aber für Enzo war er Statement und Symbol zugleich. Der V12 sollte das Herz der neuen Marke werden – kein Kompromiss, sondern ein Versprechen.

Die Entstehung des Ferrari 125 S

Basierend auf dem Colombo-V12 begann Ferrari mit dem Bau eines Prototyps: Der 125 S war geboren – benannt nach dem Hubraum jedes einzelnen Zylinders (125 cm³ x 12 = 1,5 Liter). Das Fahrzeug war ein offener Zweisitzer mit leichter Rohrrahmenkonstruktion, einem klar auf den Rennsport fokussierten Design und technischen Elementen, die für damalige Verhältnisse kühn waren: Doppelvergaser, Trockensumpfschmierung, ein neu entwickeltes 5-Gang-Getriebe.

Insgesamt wurden zwei Prototypen des Ferrari 125 S gebaut. Beide wurden in mühsamer Handarbeit gefertigt – mit einem Maß an Präzision, das Enzo Ferrari seinen Leuten einimpfte wie ein Dogma. Jeder Handschlag zählte. Jeder Fehler war einer zu viel. Man war sich bewusst, dass dies keine gewöhnlichen Autos waren – sondern die ersten Fahrzeuge, die den Namen Ferrari auf dem Kühler trugen.

Erste Tests, erste Probleme – und erste Siege

Am 12. März 1947 rollte der Ferrari 125 S erstmals unter eigener Kraft aus den Werkshallen. Testfahrer war Franco Cortese, ein erfahrener Pilot, der Enzo seit Jahren kannte. Die erste Ausfahrt verlief nicht reibungslos – der Motor überhitzte, das Getriebe zeigte Schwächen, die Lenkung war zu indirekt. Doch das störte Enzo nicht.

„Es war ein schlechter Ferrari. Aber es war ein Ferrari.“

– Enzo Ferrari über den ersten 125 S-Test

Nach einigen Wochen intensiver Überarbeitung wurde der Wagen am 11. Mai 1947 beim Grand Prix von Piacenza zum ersten Mal öffentlich eingesetzt. Cortese führte das Rennen über weite Strecken an – bis eine Benzinpumpe versagte. Enzo bezeichnete das Rennen dennoch als „vielversprechenden Misserfolg“.

Zwei Wochen später, beim Grand Prix von Rom, gelang die Revanche: Cortese siegte mit dem 125 S – der erste Sieg eines Ferrari in der Geschichte. Damit war die Marke geboren – nicht in einem Büro, nicht durch eine Unterschrift, sondern auf der Straße, unter Druck, gegen echte Konkurrenz.

Maranello als Mythos

Mit diesem Sieg begann das, was heute fast religiös verehrt wird: Die Verbindung zwischen einem Ort und einer Idee. Maranello wurde zur Geburtsstätte des Mythos Ferrari. Die kleine Werkstatt wuchs – langsam, aber stetig. Man baute weitere Fahrzeuge auf Basis des 125 S, verfeinerte den Motor, verbesserte Fahrwerk und Aerodynamik. Bald wurde nicht mehr nur für den Rennsport gebaut, sondern auch für erste wohlhabende Kunden, die sich ein Exemplar sichern wollten.

Doch Maranello blieb mehr als ein Werk. Es wurde zu einem Mikrokosmos, in dem Technik, Philosophie und Persönlichkeit verschmolzen. Jeder Mitarbeiter wusste, dass er nicht für irgendeine Firma arbeitete – sondern für eine Idee, die größer war als jedes einzelne Auto.

Der Anfang – klein, aber kompromisslos

Der „neue Anfang“ in Maranello war kein lauter Paukenschlag, sondern ein kontrollierter Zündfunke. Enzo Ferrari baute keine Autos für den Massenmarkt, keine Mittelklasse, keine Kopien. Er baute Maschinen, die Emotion, Präzision und Geschwindigkeit vereinten – kompromisslos, unnachgiebig, einzigartig.

Was 1947 begann, war mehr als nur eine Markengründung. Es war die Manifestation einer Denkweise, die bis heute Bestand hat – geboren aus Stolz, geformt aus Krieg, veredelt durch Vision. Und alles begann in einem Dorf, das vorher niemand kannte – und heute für viele das Zentrum der automobilen Welt ist.

5.2 Der Ferrari 125 S – Das erste Kind

In der Geschichte einer jeden großen Marke gibt es ein Modell, das mehr ist als ein Fahrzeug – es ist Geburtshelfer, Ikone und Leuchtfeuer zugleich. Für Ferrari ist dieses Modell der 125 S. Es war das erste Auto, das offiziell den Namen „Ferrari“ trug. Doch es war viel mehr als das: Der 125 S war ein Statement, eine Kampfansage und ein Manifest. Und er war das erste echte Kind seines Schöpfers: Enzo Ferrari.

Ein Neuanfang auf Rädern

Nach Jahren der Zurückhaltung – durch Vertragsklauseln, Krieg und Ressourcenmangel – konnte Enzo Ferrari 1947 endlich ein Fahrzeug entwickeln, das ganz ihm gehörte: konzeptionell, technisch, philosophisch. Der Ferrari 125 S war kein Abklatsch von Fiat oder Alfa Romeo. Er war etwas Neues – ein kompromisslos auf Rennsport getrimmter Prototyp, entworfen, um zu gewinnen und zu zeigen, wofür die Marke Ferrari stand.

Die „S“ in der Typbezeichnung stand für „Sport“, die 125 für den Hubraum eines einzelnen Zylinders. Multipliziert mit zwölf ergab das die Gesamtkubatur von rund 1.500 cm³ – eine archaische, fast poetische Benennung, die sich von der nüchternen Logik anderer Hersteller abhob.

Gioachino Colombo – Der Architekt des Motors

Im Zentrum des 125 S stand der Motor – ein Werk des jungen, brillanten Ingenieurs Gioachino Colombo, den Ferrari bereits zu Alfa-Zeiten kennengelernt hatte. Colombo entwickelte auf Enzos ausdrücklichen Wunsch einen kompakten V12-Motor, der nicht nur Leistung liefern sollte, sondern auch emotionaler Ausdruck war.

Die Wahl eines V12 war bemerkenswert: Für ein junges, ressourcenschwaches Unternehmen war ein solch komplexer Motor eigentlich wirtschaftlicher Wahnsinn. Doch Enzo Ferrari dachte nicht in Bilanzen, sondern in Idealen. Für ihn war der V12 ein Symbol für Raffinesse, Klangkultur und Rennpotenzial.

Der 1,5-Liter-V12 leistete anfangs rund 118 PS bei 6.800 U/min – beeindruckende Werte für die damalige Zeit. Das Triebwerk war drehfreudig, elegant konstruiert und bereits so modular ausgelegt, dass spätere Weiterentwicklungen problemlos möglich waren. Er wurde zur Grundlage für alle künftigen Ferrari-Motoren, ob auf Straße oder Strecke.

Leicht, kompromisslos, pur

Das Fahrgestell des 125 S war eine Rohrrahmenkonstruktion aus Stahl – leicht, verwindungssteif und einfach zu reparieren. Die Karosserie wurde vom Mailänder Karosseriebauer Cicognani entworfen – ein minimalistisches Design mit freistehenden Kotflügeln, ovalem Kühlergrill und tief liegendem Cockpit. Kein Zierrat, kein Luxus – nur das Nötigste, um schnell zu sein.

Technisch bot der 125 S zahlreiche Innovationen: ein Fünfgang-Getriebe – damals eine Seltenheit –, Einzelradaufhängung vorne mit Doppelquerlenkern, und eine präzise manuelle Lenkung. Das Gesamtgewicht lag unter 700 Kilogramm. Die Balance aus Leichtbau, Motorleistung und Agilität machte das Fahrzeug zu einer ernstzunehmenden Waffe auf der Rennstrecke.

Rennen als Bühne: Der erste öffentliche Auftritt

Der 125 S wurde am 11. Mai 1947 beim Grand Prix von Piacenza der Öffentlichkeit vorgestellt – ein Rennen, das Ferrari später als „vielversprechenden Misserfolg“ bezeichnete. Fahrer Franco Cortese führte lange das Feld an, bis eine defekte Benzinpumpe zum Ausfall zwang. Doch die Performance war beachtlich – vor allem, wenn man bedenkt, dass es sich um einen komplett neuen Wagen eines unbekannten Herstellers handelte.

Nur zwei Wochen später, am 25. Mai 1947, fuhr Cortese beim Grand Prix von Rom den ersten historischen Sieg für Ferrari ein. Es war nicht nur ein Rennsieg – es war die Geburt einer Legende.

Symbolische Bedeutung

Der 125 S war mehr als ein Rennwagen. Er war die materialisierte Vision von Enzo Ferrari – kompromisslos in seiner Auslegung, stolz in seiner Architektur, und durchdrungen von der Idee, dass Rennsport kein Selbstzweck ist, sondern Ausdruck einer Philosophie. Der Klang des Colombo-V12, das aufbäumende Cavallino auf der Karosserie, das Rot des Lackes – all das waren keine Stilfragen, sondern Säulen eines Mythos.

Von diesem ersten Modell ausgehend, entwickelte sich eine Linie von Fahrzeugen, die das Wesen von Ferrari bis heute prägen: Der Fokus auf Leichtbau, die Liebe zum hochdrehenden Motor, die Nähe zum Rennsport, die Exklusivität.

Der Anfang einer Ära

Der Ferrari 125 S war kein fertiges Produkt – sondern ein lebendiger Prototyp, ein Versuch, eine Haltung, ein Aufbruch. Doch er war gut genug, um zu siegen, und besonders genug, um sich von allem zu unterscheiden, was es bis dahin gab. Von nur zwei gebauten Exemplaren ist heute keiner mehr erhalten – doch der 125 S lebt weiter in jedem Ferrari, der danach gebaut wurde.

Denn wie Enzo Ferrari selbst sagte:

„Der 125 S war mein erstes Kind. Und wie alle Erstgeborenen: nicht perfekt, aber unvergesslich.“

5.3 Warum ein V12? – Mehr als nur Technik

In der Nachkriegszeit war Italien ein Land des Mangels: Rohstoffe waren knapp, Fabriken zerstört, wirtschaftliche Risiken enorm. In dieser Realität einen eigenen Sportwagen zu entwickeln, war schon mutig. Doch einen V12-Motor zu bauen – mit zwölf Zylindern, hohem Materialeinsatz und enormem Konstruktionsaufwand – grenzte an Wahnsinn. Und doch war es genau das, was Enzo Ferrari verlangte. Nicht aus technischer Notwendigkeit, sondern aus Überzeugung.

„Ich wollte, dass meine Autos eine Stimme haben, die man erkennt – auch mit geschlossenen Augen.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Der Klang als Signatur

Für Ferrari war ein V12 keine technische Entscheidung, sondern eine künstlerische. Er war besessen vom Klang eines Motors – nicht nur als Nebeneffekt, sondern als Seele der Maschine. Der Colombo-V12, der im 125 S debütierte, produzierte eine hochfrequente, fast orchestrale Klangkulisse – geschmeidig, vibrierend, mechanisch perfekt ausbalanciert. Es war Musik aus Metall, ein Ausdruck italienischer Ingenieurskunst und Leidenschaft.

In einer Zeit, in der die meisten Konkurrenten auf Vierzylinder- oder Reihen-Sechszylinder setzten, wirkte Ferraris Entscheidung elitär – und das war durchaus beabsichtigt. Der V12 war ein Statement der Differenz.

Balance, Leistung, Prestige

Neben dem Klang sprach auch die Leistungscharakteristik für einen V12: Durch die Verteilung der Verbrennungsvorgänge auf mehr Zylinder lief der Motor ruhiger, drehte freier hoch und erlaubte bei gleichem Hubraum ein höheres Drehzahlniveau. Das bedeutete nicht nur mehr Spitzenleistung, sondern auch bessere Fahrbarkeit, gerade in Grenzbereichen.

Gleichzeitig war der V12 eine Frage des Prestiges. In den 1930ern war der Zwölfzylinder den Luxusmarken vorbehalten – Bugatti, Packard, Hispano-Suiza. Enzo Ferrari wollte nicht in der Masse untergehen, sondern sich ganz oben einordnen. Seine Botschaft: Ferrari ist keine kleine Werkstatt – Ferrari ist Klasse.

Ein Motor als Philosophie

Der Colombo-V12 wurde zur ideologischen Grundlage der Marke. Er war modular, skalierbar, weiterentwickelbar – aber vor allem: ein Symbol. In den kommenden Jahrzehnten sollte er in dutzenden Modellen erscheinen, von Rennwagen bis Straßenfahrzeugen, und so den akustischen und technischen Herzschlag Ferraris definieren.

Der V12 war keine Antwort auf die Frage, wie man schneller wird.

Er war die Antwort auf die Frage: Wie fühlt sich Geschwindigkeit an?

5.4 Die ersten Mitarbeiter – Der Geist von Maranello

Wenn ein Unternehmen wie Ferrari entsteht, denken viele zuerst an Motoren, Fahrzeuge und Rennen. Doch in Wahrheit sind es immer die Menschen hinter der Maschine, die aus Technik eine Legende formen. Und in Maranello – diesem kleinen Ort mit großer Zukunft – versammelte Enzo Ferrari ab 1945 eine Gruppe von Persönlichkeiten, die mehr waren als nur Mitarbeiter: Sie waren Mitstreiter, Pioniere, Vertraute.

Ein Team wie ein Uhrwerk

Ferrari stellte seine ersten Mitarbeiter nicht wegen ihrer Abschlüsse ein, sondern wegen ihres Charakters. Er suchte Menschen, die absoluten Einsatz zeigten – Tag und Nacht, unter Zeitdruck, bei Rückschlägen. Viele von ihnen kamen aus der Region, manche kannte Enzo noch aus Alfa-Zeiten, andere waren junge, hungrige Talente.

Da war zum Beispiel Luigi Bazzi, ein langjähriger Ingenieur und Ferraris rechter Hand in technischen Fragen. Oder Franco Gozzi, später Pressechef und enger Vertrauter, der Enzo jahrzehntelang begleitete. Und natürlich Gioachino Colombo, der den berühmten V12 konstruierte – mit ruhiger Hand, klarem Kopf und musikalischem Gespür für Mechanik.

Diese Männer und viele weitere bildeten das Fundament dessen, was Ferrari nannte: „La mia famiglia tecnica“ – meine technische Familie.

Disziplin, Stolz, Hingabe

Die Arbeit in Maranello war kein gewöhnlicher Job. Es war ein Bekenntnis. Die Anforderungen waren hoch, die Arbeitszeiten lang, der Chef fordernd. Fehler wurden nicht toleriert, Mittelmaß ebenso wenig. Doch wer sich bewährte, wurde Teil von etwas Größerem.

„Ich habe nicht nach Genies gesucht, sondern nach Menschen mit unstillbarem Ehrgeiz.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Aus dieser Kultur entstand der sogenannte Geist von Maranello – eine Mischung aus Besessenheit, Präzision, Kameradschaft und stillem Stolz. Ein Geist, der bis heute in jeder Halle, jeder Schraube, jedem Startknopf spürbar ist.

5.5 Erste Kunden, erste Legenden

Als Enzo Ferrari 1947 den ersten Rennsieg mit dem 125 S errang, war klar: Die Technik funktionierte, die Vision lebte. Doch es war auch offensichtlich, dass reiner Rennsport allein nicht reichen würde, um das Unternehmen wirtschaftlich zu tragen. Enzo war kein Träumer ohne Realitätssinn – er wusste, dass Ferrari sich öffnen musste. Nicht für jeden, aber für die Richtigen.

Der erste Kunde – eine Freundschaft mit Folgen

Der erste offizielle Kunde von Ferrari war Cav. Antonio D'Amico, ein sizilianischer Adeliger mit Benzin im Blut. Er bestellte einen Sportwagen, der auf dem 125 S basierte, aber straßentauglich gemacht wurde. Das Fahrzeug wurde als Ferrari 159 S ausgeliefert – mit überarbeitetem V12, Karosserie von Touring und einem Hauch von italienischem Luxus.

Es war der Beginn eines neuen Zweigs: Ferrari begann, Straßenfahrzeuge auf Renntechnikbasis zu fertigen – in Kleinstauflagen, maßgeschneidert für Liebhaber mit dem nötigen Kapital und dem richtigen Ruf. Für Enzo Ferrari war es wichtig, dass seine Kunden nicht nur Käufer, sondern auch Botschafter waren.

Exklusivität als Strategie

Ferrari verkaufte keine Autos „an jeden“. Noch in den 1950ern entschied Enzo persönlich, wer ein Fahrzeug bekommen durfte. Er verlangte Diskretion, Begeisterung, Stil – und die Bereitschaft, sich dem Mythos unterzuordnen. Ein Ferrari war kein Statussymbol, er war eine Eintrittskarte in eine Idee.

„Ich verkaufe nicht einfach Autos – ich wähle meine Kunden.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Legenden der ersten Stunde

Unter den frühen Kunden fanden sich Rennfahrer, Künstler, Industrielle. Namen wie Luigi Chinetti, Pierre-Louis-Dreyfus, Count Gianni Marzotto – sie fuhren nicht nur Ferrari, sie gewannen mit Ferrari. Und sie machten die Marke auf internationalen Rennstrecken und bei mondänen Anlässen gleichermaßen bekannt.

So wurden aus Käufern Kollaborateure – und aus jedem verkauften Auto ein weiteres Kapitel Ferrari-Geschichte.

5.6 Der internationale Durchbruch

Ende der 1940er-Jahre war Ferrari in Italien bereits eine aufstrebende Größe. Die Siege auf der Rennstrecke, das Aufsehen um den Ferrari 125 S, der mutige Einsatz eines V12 – all das hatte Eindruck gemacht. Doch Enzo Ferrari dachte größer. Für ihn war Italien nur die Startrampe. Sein Ziel war es, Ferrari auf den internationalen Rennstrecken und Luxusmeilen zu etablieren – als Symbol für Exzellenz, Leistung und italienische Ingenieurskunst.

Der Weg dorthin war weder geradlinig noch einfach. Es war ein Zusammenspiel aus strategischen Partnerschaften, Rennsportmarketing, einzigartiger Technik und einer Prise italienischer Theatralik, die Ferrari schließlich zu dem machten, was die Marke heute ist: ein globaler Mythos auf vier Rädern.

Luigi Chinetti – Der Mann, der Ferrari nach Amerika brachte

Ein Name, der mit Ferraris weltweitem Aufstieg untrennbar verbunden ist, ist Luigi Chinetti. Der gebürtige Italiener war in den 1920er- und 1930er-Jahren selbst Rennfahrer gewesen, hatte unter anderem zweimal Le Mans gewonnen und war während des Zweiten Weltkriegs in die USA emigriert. Chinetti war nicht nur ein Enthusiast, sondern ein brillanter Verkäufer mit einem untrüglichen Gespür für Luxus und Motorsport.

Er erkannte früh das Potenzial, das Ferrari in Übersee haben könnte – insbesondere bei wohlhabenden Amerikanern, die von europäischen Exoten fasziniert waren. 1949 kam es zu einem Schlüsselmoment: Chinetti nahm an den 24 Stunden von Le Mans teil – auf einem Ferrari 166 MM Barchetta, den er sich buchstäblich „erschnorrt“ hatte.

Er gewann.

Dieser Sieg war Ferraris erster großer internationaler Erfolg – und er machte Wellen. Plötzlich stand der Name Ferrari nicht nur in italienischen Zeitungen, sondern auf den Titelseiten der internationalen Motorsportpresse. Das Echo war gewaltig – ein neuer Stern war geboren.

Ferrari goes USA – Die Gründung von Ferrari North America

Nach dem Le-Mans-Sieg überzeugte Chinetti Enzo davon, ihn zum exklusiven Importeur für Nordamerika zu machen. Enzo, der das kommerzielle Geschäft nicht sonderlich mochte, überließ ihm große Freiheiten. 1950 gründete Chinetti in New York Ferrari North America – lange bevor andere europäische Marken den US-Markt ernsthaft anvisierten.

Er verkaufte die Autos nicht über große Händlerketten, sondern über exklusive Salons, gezielte Kundengespräche und persönliche Empfehlungen. Ferrari wurde nicht als Auto präsentiert – sondern als Kunstwerk, als Geheimtipp, als Teil einer elitären Welt.

Der Plan ging auf. In den 1950er-Jahren entwickelte sich Ferrari in den USA zum Inbegriff von Raffinesse und motorsportlicher Aura. Hollywood-Schauspieler, Musiker, Geschäftsleute – sie alle wollten einen Ferrari. Nicht weil sie ihn brauchten, sondern weil er mehr versprach als nur Geschwindigkeit.

Motorsport als Weltsprache

Während Chinetti im Westen Türen öffnete, sorgte Ferrari auf den Rennstrecken Europas und der Welt für Furore. In den 1950er-Jahren dominierte die Marke unter anderem bei der Mille Miglia, der Targa Florio, dem Großen Preis von Monaco und natürlich immer wieder in Le Mans.

Fahrzeuge wie der Ferrari 166, der 250 S, später der 375 MM oder der 750 Monza trugen zum Ruf der Marke bei – ebenso wie legendäre Fahrer: Alberto Ascari, Juan Manuel Fangio, Phil Hill, Luigi Musso, Mike Hawthorn und viele andere prägten das internationale Bild von Ferrari als dominierende Kraft.

Doch es ging nicht nur um Siege. Es ging um Stil. Ferrari trat auf wie eine Oper auf Rädern: rot, laut, dramatisch, elegant. Selbst wenn man nicht gewann, war Ferrari präsent – durch Ausstrahlung, Design und ein unverkennbares Geräusch.

Der Ferrari 250 – Das globale Meisterstück

Einen besonderen Anteil am internationalen Durchbruch hatte ab Mitte der 1950er-Jahre die Modellreihe Ferrari 250 – insbesondere der 250 GT Berlinetta und später der 250 GTO. Diese Fahrzeuge vereinten erstmals kompromisslose Renntechnik mit straßentauglicher Eleganz. Sie waren schnell, schön und rar – eine Kombination, die Sammler und Sportwagenliebhaber auf der ganzen Welt elektrisierte.

Die GTO-Version gilt heute als das wertvollste Auto der Welt, mit Auktionspreisen jenseits der 50 Millionen US-Dollar. Damals war er der Wagen, mit dem sich Ferrari in Europa, Nordamerika und sogar Südamerika endgültig als Synonym für Hochleistung und Exklusivität etablierte.

Exklusivität und Mythos – gezielt gesteuert

Was viele nicht wissen: Der weltweite Erfolg Ferraris war nicht nur das Ergebnis von Technik und Siegen, sondern einer bewussten, fast visionären Markenpolitik. Enzo Ferrari weigerte sich beharrlich, in großen Stückzahlen zu produzieren. Jeder Ferrari war ein Einzelstück, ein Unikat, eine Auszeichnung für den Käufer.

Er wählte Kunden persönlich aus, stellte Fahrzeuge individuell zusammen, ließ sogar Sonderanfertigungen bauen. Das steigerte nicht nur die Nachfrage – es schuf eine Aura der Unnahbarkeit, die den Mythos bis heute nährt.

„Jeder Ferrari ist ein Geschenk an jemanden, der ihn verdient.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Der Cavallino galoppiert um die Welt

Mit jedem Sieg, jedem Neuwagen, jedem Artikel in der internationalen Presse wurde das springende Pferd – das Cavallino Rampante – bekannter. Es wurde zur globalen Ikone, vergleichbar mit der Rolex-Krone oder dem Mercedes-Stern. Der Unterschied: Ferrari war nie Massenware. Und genau das machte ihn zur Legende.

Maranello wurde in den 1950ern zum Wallfahrtsort für Motorsportfans aus aller Welt. Händler, Rennteams, Journalisten, Prominente – alle pilgerten in das bescheidene Werk, um einen Blick auf den Mann, die Marke und die Maschinen zu werfen, die in nur wenigen Jahren den Globus erobert hatten.

Vom Rennstall zur Weltmarke

Der internationale Durchbruch Ferraris war kein Zufall, sondern das Ergebnis strategischer Weitsicht, kompromissloser Technik und emotionaler Markenführung. Enzo Ferrari verstand, dass Rennsiege nur der Anfang waren – entscheidend war, daraus eine Erzählung zu machen, die man über Kontinente hinweg hören und fühlen konnte.

Und so wurde Ferrari in nur wenigen Jahren von einem kleinen Rennstall in Maranello zu einer globalen Religion für Autofans, Sammler, Ästheten und Träumer.

Kapitel 6: Enzo Ferrari als Unternehmer, Perfektionist und Kontrollfreak

Enzo Ferrari war mehr als ein Unternehmer. Er war ein Dirigent, ein Architekt, ein Patriarch – und oft auch ein Diktator in seinem eigenen Imperium. Wer das Wesen der Marke Ferrari verstehen will, muss zuerst den Mann dahinter begreifen: einen Menschen, der Kontrolle über alles forderte, was seinen Namen trug – von der Zündkerze bis zur Pressemitteilung. Für Enzo war die Firma kein Unternehmen im klassischen Sinn, sondern eine Verlängerung seiner Persönlichkeit.

Während andere Firmen Hierarchien und Gremien aufbauten, ließ Enzo Entscheidungen auf seinem Schreibtisch enden. Während andere Marken mit Werbung warben, ließ Ferrari die Welt raten, ob man einen seiner Wagen überhaupt kaufen durfte. Er vertraute niemandem ganz – nicht seinen Fahrern, nicht der Presse, nicht einmal seinen Ingenieuren. Und doch zog er die besten Köpfe der Branche an, weil sie wussten: Wer hier arbeitet, schreibt Geschichte.

Dieses Kapitel beleuchtet den Menschen Enzo Ferrari jenseits des Rennsports – als Unternehmer, als Perfektionist, als Kontrollfreak. Eine komplexe Persönlichkeit, deren Schattenseiten ebenso zum Mythos gehören wie ihre Genialität.

6.1 Die Marke war er selbst – Ferraris Führungsstil

Enzo Ferrari war kein Manager im modernen Sinn. Er schrieb keine Leitbilder, gründete keine HR-Abteilungen und formulierte keine Change-Strategien. Stattdessen herrschte er – mit Intuition, Instinkt, Strenge und einer Prise kalkulierter Unnahbarkeit. Die Marke Ferrari war nie ein anonymes Unternehmen, sondern ein Spiegelbild seines Gründers. Und dieser spiegelte etwas wider, das ebenso faszinierend wie furchteinflößend war: totale Kontrolle, absolute Hingabe und eine fast religiöse Vorstellung von Disziplin.

Ein Büro wie eine Kommandozentrale

Wer in den 1950er- oder 1960er-Jahren das Ferrari-Werk in Maranello betrat, kam an einem Ort nicht vorbei: Enzos Büro. Es war nicht pompös – eher funktional, fast asketisch. Doch es war der Mittelpunkt eines komplexen Systems. Jeder Brief, jede Entscheidung, jede technische Spezifikation lief über seinen Tisch. Nichts verließ das Werk ohne seine Zustimmung.

Mitarbeiter beschrieben seinen Raum als still, aber schwer von Erwartung. Wer vorgeladen wurde, wusste: Man kommt nicht zum Plaudern. Gespräche waren kurz, klar und von oben herab. Kritik war die Norm, Lob eine Seltenheit – und genau das machte jede Anerkennung von ihm umso bedeutungsvoller.

Zentralismus als Prinzip

Ferrari glaubte nicht an Delegation im klassischen Sinn. Zwar hatte er brillante Köpfe in Technik und Management um sich – etwa Mauro Forghieri, Carlo Chiti oder Franco Gozzi –, doch die letzte Entscheidung lag immer bei ihm. Ob es um neue Fahrzeugentwicklungen, Fahrerverträge, Marketingentscheidungen oder Rennstrategien ging: Enzo entschied. Und seine Entscheidungen waren nicht immer rational.

Er war berüchtigt dafür, Projekte über Nacht zu kippen, Designvorgaben zu verwerfen oder Testberichte zu ignorieren – nicht aus Laune, sondern aus Überzeugung. Er vertraute auf seine Intuition, auf das Bauchgefühl eines Mannes, der sich selbst für unfehlbar hielt, solange er seinem inneren Kompass folgte.

„Ich baue keine Autos für Kunden. Ich baue Autos, wie ich sie mir vorstelle – und wenn sie jemand kaufen will, umso besser.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Distanz als Werkzeug der Kontrolle

Ferrari war in seinem Unternehmen allgegenwärtig – und gleichzeitig schwer greifbar. Er mischte sich in jede Abteilung ein, konnte jeden Mechaniker beim Vornamen nennen, und doch blieb er auf eine eigentümliche Weise unnahbar. Diese Distanz war keine Charakterschwäche, sondern eine bewusste Strategie: Sie schuf Autorität.

Er verteilte Aufgaben oft vage, gab keine vollständige Information weiter und setzte Teams indirekt unter Druck – auch, um Rivalitäten zu fördern. „Konkurrenz im Haus“ war für ihn kein Problem, sondern ein Antrieb. Er ließ Konstrukteure bewusst gegeneinander arbeiten, testete alternative Lösungen parallel und entschied sich oft spät – nach Bauchgefühl, nicht nach Daten.

Loyalität über alles

Wer bei Ferrari arbeiten wollte, musste sich auf mehr einlassen als technische Exzellenz: bedingungslose Loyalität war Voraussetzung. Wer sich kritisch über Entscheidungen äußerte, wer mit Journalisten sprach oder gar intern Meinungen hinterfragte, musste mit Konsequenzen rechnen – vom Ausschluss wichtiger Meetings bis zur Entlassung.

Dennoch gab es Mitarbeiter, die ihm jahrzehntelang die Treue hielten. Sie verstanden, dass die Härte kein Selbstzweck war, sondern Teil eines größeren Ganzen: Enzo Ferrari formte nicht einfach Fahrzeuge – er formte Charaktere. Wer bei ihm bestehen wollte, wurde besser. Oder ging unter.

Die Fahrer als Soldaten

Besonders deutlich wurde Ferraris Führungsstil im Umgang mit seinen Rennfahrern. Er nannte sie „meine Soldaten“ – Männer, die in seine Autos stiegen, um für die Ehre der Scuderia zu kämpfen. Persönliche Bindung hielt er auf Distanz. Selbst seine erfolgreichsten Piloten, wie Alberto Ascari oder Gilles Villeneuve, berichteten, dass sie nie wirklich „nah“ an Enzo herankamen.

Verträge wurden jährlich neu verhandelt. Fahrer wurden entlassen, wenn sie ihm zu eigenständig oder unbequem wurden – auch dann, wenn sie gerade Titel geholt hatten. Die Botschaft war klar: Niemand steht über Ferrari.

Das führte zu einer Mischung aus Angst und Verehrung. Fahrer kämpften nicht nur gegen ihre Gegner auf der Strecke – sondern auch um Anerkennung beim Mann im Büro über dem Innenhof.

Eine Marke als Selbstportrait

Enzo Ferrari verstand früh, dass die größte Kraft seiner Firma nicht nur in Technik oder Performance lag – sondern in der Emotionalisierung. Er wusste, dass Käufer nicht nur schnelle Autos suchten, sondern ein Gefühl. Ein Mythos. Ein Versprechen. Und so wurde Ferrari zum Selbstporträt seines Gründers: elegant, leidenschaftlich, unnachgiebig.

Die Marke Ferrari trug Enzos Handschrift bis in die Details:

Das springende Pferd als Wappen einer Idee

Der V12 als akustisches Erkennungszeichen

Die rote Farbe als Symbol italienischer Kraft

Die Exklusivität als Schutzschild gegen Beliebigkeit

Führung durch Präsenz, nicht durch Prozesse

Enzo Ferrari war kein moderner CEO, kein Diplomat und kein Stratege im klassischen Sinn. Er war ein Mann, der ein Unternehmen durch reine Präsenz führte – mit wachem Blick, unerbittlicher Erwartung und einem festen inneren Kodex. Seine Mitarbeiter, seine Ingenieure und seine Kunden spürten, dass sie nicht Teil einer Firma waren – sondern Teil einer Idee, die größer war als sie selbst.

Und diese Idee hatte ein Gesicht: das von Enzo Ferrari.

6.2 Kontrolle, Misstrauen und Macht – Die dunkle Seite der Perfektion

Enzo Ferrari war zweifellos ein Visionär – aber auch ein Mann, dessen Streben nach Kontrolle oft zu einem Klima aus Unsicherheit, Angst und Manipulation führte. Wer für Ferrari arbeitete, spürte schnell: Hier zählt Leistung – aber noch mehr zählt Loyalität. Und wer nicht in sein Weltbild passte, wurde ausgewechselt wie ein defekter Kolben. Die dunkle Seite seines Perfektionismus war ein Umfeld, in dem Vertrauen nicht geschenkt, sondern maximal getestet wurde.

Misstrauen als Prinzip

Ferrari traute grundsätzlich niemandem vollständig – weder seinen Technikern noch seinen Fahrern, Geschäftspartnern oder Journalisten. Dieses Grundmisstrauen war nicht Ausdruck von Paranoia, sondern von tiefer Überzeugung: Vertrauen macht verletzlich. Kontrolle schützt.

Er kontrollierte alles: Briefe an Lieferanten, Pressemitteilungen, Fahrzeugdaten, sogar interne Gespräche. Manche Mitarbeiter berichteten, dass er gelegentlich Spitzel im eigenen Haus platzierte – Personen, die Gespräche mitlauschten und informell zurückmeldeten, was hinter den Kulissen gesprochen wurde.

„Ich will wissen, was in meinem Haus gesagt wird, bevor es draußen jemand erfährt.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Die Struktur in Maranello war nicht flach, sondern vertikal und intransparent. Informationsfluss war bewusst limitiert, um Abhängigkeiten zu schaffen. Wer etwas wissen wollte, musste es sich verdienen – oder warten, bis Enzo es preisgab.

Macht durch Unsicherheit

Ferrari glaubte, dass Menschen unter Druck besser funktionieren. Dieses Prinzip galt nicht nur für Rennfahrer, sondern auch für Konstrukteure, Testfahrer, Buchhalter. Ein Zustand permanenter Unsicherheit erzeugte in seinen Augen Leistung, Kreativität und Loyalität.

Ein beliebtes Werkzeug war die gezielte Entmachtung von Schlüsselpersonen, sobald sie zu viel Einfluss gewannen. Enzo ließ Abteilungen bewusst gegeneinander arbeiten, förderte interne Konkurrenz, vermied klare Zuständigkeiten. Mancher Ingenieur wurde nach erfolgreichen Projekten auf Nebenschauplätze verschoben – um zu verhindern, dass ihm zu viel Ruhm zufiel.

Selbst die besten Rennfahrer wurden nie hofiert, sondern herausgefordert – psychologisch wie technisch. Neue Fahrer wurden regelmäßig „getestet“, indem man sie mit schlechterem Material versorgte oder in entscheidenden Momenten im Dunkeln ließ.

Ferraris „Regime“ in der Rennabteilung

Am sichtbarsten war Ferraris Machtstrategie in der Scuderia, seinem Rennteam. Dort herrschte ein Klima wie im Militär: absolute Disziplin, kaum Freiraum, harte Konsequenzen für Fehler. Der Zugang zu Enzo selbst war limitiert. Fahrer durften selten direkt mit ihm sprechen. Entscheidungen fielen spät – manchmal erst am Renntag – und wurden nicht diskutiert.

Selbst Weltmeister wie Alberto Ascari oder John Surtees berichteten von Enttäuschungen, Isolation und bewusster Provokation. Surtees, der Ferrari 1964 den Titel holte, wurde ein Jahr später de facto hinausgedrängt, weil er sich mit technischen Entscheidungen nicht einverstanden zeigte.

„Er gab dir Flügel – und schnitt sie dir ab, wenn du zu hoch flogst.“

– John Surtees über Enzo Ferrari

Enzo betrachtete Fahrer als Ersatzteile – wichtig, aber austauschbar. Er sprach nie öffentlich über persönliche Bindung, obwohl er einzelne Fahrer sehr wohl schätzte. Doch Nähe wurde selten zugelassen. Sie bedeutete Kontrollverlust.

Tragödien – und die Frage nach Verantwortung

Ferraris Ruf als Kontrollfreak wurde durch eine Reihe tragischer Ereignisse überschattet – allen voran der Tod mehrerer Fahrer unter seiner Ägide. Besonders in den 1950er- und 1960er-Jahren starben zahlreiche Piloten in Ferrari-Wagen, darunter:

Alberto Ascari (1955) – wenn auch nicht im Ferrari

Eugenio Castellotti (1957)

Luigi Musso (1958)

Peter Collins (1958)

Wolfgang von Trips (1961) – zusammen mit 15 Zuschauern in Monza

Nach dem Tod von Collins und Musso innerhalb weniger Wochen wurde Enzo Ferrari in der Presse als „il costruttore di morte“ – der Todesmacher bezeichnet. Ihm wurde vorgeworfen, Fahrer in Duelle zu schicken, die sie menschlich nicht durchstehen konnten. Der interne Konkurrenzdruck, den er gezielt schürte, sei mitverantwortlich für riskante Fahrmanöver.

Ferrari wies jede Schuld von sich. In seinen Augen waren es die Fahrer selbst, die Risiken eingingen – aus Ehrgeiz, nicht auf seinen Befehl. Doch intern wurde deutlich, dass Enzos System auf psychologischer Erpressung beruhte: Wer schwächelte, flog. Wer siegte, durfte bleiben – bis der nächste kam.

Ferrari und Frauen – Distanz statt Nähe

Eine weitere Facette von Enzos Misstrauen zeigte sich im Umgang mit Frauen, insbesondere im Beruf. Ferrari beschäftigte nur wenige Frauen in seinem Unternehmen, und fast nie in Schlüsselpositionen. Er war geprägt von einem patriarchalischen Weltbild, das wenig Platz für emotionale oder gleichwertige Bindungen ließ – beruflich wie privat.

Auch mit seiner eigenen Familie hielt er emotionale Distanz: Seine Ehefrau Laura war über Jahre hinweg kaum in das Unternehmen eingebunden, sein Sohn Dino wuchs in einem Umfeld aus Kontrolle und Erwartung auf, das ihn psychisch wie physisch belastete. Erst Dinos Tod sollte in Enzo eine sichtbare Wunde hinterlassen – und zu einem der wenigen Momente führen, in dem die Öffentlichkeit Emotionen jenseits der Bühne wahrnahm.

Mythos trotz – oder wegen – der Härte?

Rückblickend stellt sich die Frage: War Enzo Ferraris rigides, misstrauisches System der Preis für den Erfolg? Oder war es genau dieses System, das Ferrari zu dem gemacht hat, was es ist – eine Marke, die nicht mit Masse, sondern mit Mythen arbeitet?

Es ist schwer zu sagen. Viele Weggefährten berichten mit Respekt, aber ohne Wärme. Kaum jemand beschreibt Enzo als freundlich. Aber alle betonen seine Präsenz, seine Konsequenz und seine Besessenheit von Qualität. Vielleicht ist genau das die Antwort: Ferrari wurde zur Ikone nicht trotz Enzos dunkler Seiten – sondern wegen ihnen.

Enzos Kontrolle schuf Größe – aber auch Leid

Enzo Ferrari formte eine Marke wie ein Bildhauer: mit präzisem Meißel, aber ohne Rücksicht auf die Steinsplitter, die dabei fielen. Kontrolle war seine Richtschnur, Misstrauen sein Werkzeug, Macht seine Absicherung. Er erschuf etwas Unsterbliches – aber hinter dem Mythos liegen viele gebrochene Karrieren, enttäuschte Erwartungen und Träume, die zu Staub wurden.

Ferrari war Perfektion. Und Perfektion ist selten warm.

6.3 Der Mythos als Produkt – Marketing ohne Marketing

In einer Welt, in der sich Marken mit Hochglanzanzeigen, Werbeslogans und Millionenbudgets ins kollektive Bewusstsein brennen, fällt Ferrari aus dem Raster. Enzo Ferrari lehnte klassische Werbung ab – nicht aus Unwissenheit, sondern aus Überzeugung. Für ihn galt: Ein Ferrari erklärt sich nicht. Ein Ferrari zeigt sich. Er sah sein Produkt nicht als Konsumgut, sondern als Kunstwerk, das durch seine pure Existenz Aufmerksamkeit erzeugt.

Was für andere Marken Marketingabteilungen erledigten, erledigte bei Ferrari der Mythos selbst. Und dieser Mythos war kein Zufall, sondern ein sorgfältig komponiertes Meisterwerk – aus Siegen, Seltenheit, Schönheit und Legendenbildung.

1. Keine Werbung, keine Rabatte, kein Verkaufsgespräch

Enzo Ferrari hatte ein eher elitäres Verständnis von Luxus. Für ihn bedeutete Luxus nicht Überfluss, sondern Verknappung. Seine Fahrzeuge waren nicht da, um verkauft zu werden – sie waren da, um verlangt zu werden. Der Käufer musste sich dem Produkt nähern, nicht umgekehrt.

Er ließ nie klassische Anzeigen in Zeitungen schalten. Er produzierte keine Broschüren für Autohäuser. Es gab kein Ferrari-Logo auf Straßenbahnen, keine TV-Spots. Und vor allem: keine Rabatte. Wer einen Ferrari wollte, musste nicht nur das Geld haben – sondern auch das Ansehen, die Geduld und das Verständnis, dass dieses Auto mehr war als ein Fortbewegungsmittel.

„Ich verkaufe keine Autos. Ich verkaufe Träume, die man nicht konfigurieren kann.“

– Enzo Ferrari

2. Der Rennsport als Bühne

Der wichtigste Marketingkanal war – von Beginn an – der Rennsport. Für Enzo war ein Sieg bei Le Mans oder Monza wertvoller als tausend Werbeanzeigen. Denn im Rennen zeigt sich die Wahrheit: über Technik, über Mut, über Qualität. Ferrari investierte Unsummen in den Motorsport, nicht nur als Mittel zur technischen Entwicklung, sondern als medialen Resonanzraum.

Jeder Sieg wurde zum Beweis: Ferrari ist schneller, besser, überlegen. Und diese Botschaft wirkte tief – selbst auf Menschen, die nie ein Rennen besuchten. Die Namen der Rennfahrer, die rohen V12-Klänge, die Bilder der roten Wagen im Drift – sie brannten sich in das kulturelle Gedächtnis ein.

„Unsere Kunden kaufen keine Autos – sie kaufen einen Anteil an unseren Siegen.“

– Enzo Ferrari

3. Verknappung als Verkaufsstrategie

Ein weiterer zentraler Pfeiler von Ferraris Markenführung war die künstliche Verknappung. Selbst in wirtschaftlich starken Zeiten baute Ferrari nie „zu viele“ Autos. Die Produktion blieb überschaubar, selektiv, kontrolliert. Nicht jeder Händler durfte Ferrari verkaufen. Nicht jeder Kunde bekam einen.

Gerüchten zufolge ließ Enzo Ferrari sogar Anfragen ablehnen – selbst von Prominenten oder reichen Geschäftsleuten –, wenn er sie für „nicht passend“ hielt. Die Botschaft war klar: Ein Ferrari sucht sich seinen Fahrer aus, nicht umgekehrt.

Diese Strategie erzeugte das, was alle Luxusmarken suchen: Begierde durch Ausschluss. Wer keinen Ferrari bekam, wollte einen umso mehr.

4. Design als emotionale Waffe

Ein Ferrari war nie nur schnell – er war auch eine Skulptur auf Rädern. Enzo Ferrari arbeitete mit den besten Karosseriebauern Italiens zusammen: Pininfarina, Scaglietti, Touring Superleggera, Bertone. Jeder Entwurf war mehr als ein Gehäuse – er war eine Inszenierung.

Die Linienführung eines Ferrari war immer dramatisch: langgezogene Motorhaube, muskulöse Radkästen, aggressiver Blick. Selbst im Stand vermittelte er das Gefühl von Geschwindigkeit. Es war kein Zufall, dass Ferrari-Modelle in den 1950er- und 60er-Jahren mehrfach Kunstpreise gewannen – nicht für Technik, sondern für Ästhetik.

Ferraris Botschaft lautete: Unsere Autos sind Kunstwerke, keine Produkte.

5. Der Mythos Ferrari als Medienmagnet

Enzo Ferrari verstand es, sich selbst und sein Unternehmen zur Geschichte zu machen. Er gab selten Interviews – und wenn, dann spärlich, verschlüsselt, mit langen Pausen und Andeutungen. Die Presse nannte ihn den „Commendatore“ oder den „Drachen von Maranello“. Er ließ Journalisten warten, er entzog sich, er umgab sich mit Geheimnissen.

Gerade diese Zurückhaltung erzeugte das Gegenteil von Desinteresse: Ferrari war ständig in den Schlagzeilen, weil das, was nicht gesagt wurde, oft interessanter war als das Gesagte. Jede neue Modellankündigung, jeder Fahrerwechsel, jedes Rennen wurde medial aufgegriffen wie ein Kapitel aus einem Epos.

„Ich habe nie um Aufmerksamkeit gebeten. Aber ich wusste immer, wie man sie erzeugt.“

– Enzo Ferrari

6. Das Cavallino Rampante – Ein Logo mit Seele

Das springende Pferd – das „Cavallino Rampante“ – wurde zu einem der bekanntesten Logos der Welt. Es stand nicht nur für Ferrari, sondern für eine Idee: italienische Leidenschaft, ungezähmte Kraft, Stolz.

Enzo Ferrari platzierte es nicht großflächig oder aufdringlich – es war meist klein, elegant, aber unübersehbar. Das Pferd wurde nicht einfach als Marke behandelt, sondern als Siegel. Wer es trug – sei es auf dem Lenkrad, auf der Brust oder im Pass –, gehörte zu einer Elite.

Bis heute steht das Logo für mehr als eine Marke. Es steht für Stil, Leistung, Haltung und Geschichte. Kein anderes Emblem vermittelt so viel Mythos mit so wenigen Linien.

Der Mythos Ferrari war kein Zufall

Ferrari ist eine der bekanntesten und begehrtesten Marken der Welt – und doch wurde sie nie durch klassische Werbung aufgebaut. Enzo Ferrari verstand, dass echte Begehrlichkeit nicht gekauft, sondern kultiviert wird. Durch Siege. Durch Verknappung. Durch Inszenierung. Und durch kompromisslose Qualität.

Er machte seine Marke zu einem Mythos – und dieser Mythos machte ihn unsterblich. Bis heute gilt: Ein Ferrari ist kein Auto. Es ist ein Gefühl. Und dieses Gefühl braucht keine Anzeige – nur einen Motor, ein Emblem und eine Geschichte.

6.4 Das Enigma Ferrari – Genie und Widerspruch

Enzo Ferrari war ein Mann voller Gegensätze. Ein Visionär mit klarem Ziel – und doch jemand, der vieles im Dunkeln ließ. Ein Mann der Technik, der gleichzeitig über Intuition entschied. Ein Patriot, der sich von seiner Heimat distanzierte. Ein Familienvater, der sich emotional verschloss. Ein Mythenschöpfer, der selbst zum Mythos wurde.

In ihm vereinten sich Licht und Schatten. Und genau diese Widersprüchlichkeit macht ihn bis heute so faszinierend – für Bewunderer, Kritiker und Historiker gleichermaßen.

Ein Mann der Öffentlichkeit, der sich ihr entzog

Trotz seines übergroßen Einflusses auf die Automobilwelt und der stetigen Präsenz der Marke Ferrari in den Medien, blieb der Mensch Enzo Ferrari weitgehend ein Rätsel. Er war öffentlich bekannt, aber nie wirklich zugänglich. Er zeigte sich selten auf Veranstaltungen, gab nur ausgewählten Journalisten Interviews und trat nie bei Preisverleihungen auf. Selbst bei Siegen seiner Fahrer war es ungewöhnlich, ihn auf dem Podium oder im Fahrerlager zu sehen.

„Ich bin kein Mann der Bühne. Die Autos sprechen für mich.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Er zog es vor, in seinem Büro in Maranello zu bleiben – stets in Reichweite, aber nie mittendrin. Besucher berichteten von Gesprächen, die sich wie Audienzen anfühlten: kurz, bestimmt, ohne Smalltalk. Wer sich ihm gegenüber in Szene setzen wollte, hatte verloren.

Charismatisch und kalt zugleich

Trotz dieser Distanz war Enzo Ferrari eine charismatische Figur. Er besaß diese stille Autorität, die ohne Lautstärke auskam. Mitarbeiter sagten, dass seine bloße Anwesenheit in einem Raum die Temperatur senkte – und zugleich die Spannung steigerte. Er war ein Mann, dem man folgen wollte – auch wenn man ihn nie ganz verstand.

Er konnte inspirierend sein, fast väterlich – vor allem gegenüber jungen Ingenieuren oder talentierten Fahrern. Doch dieselbe Wärme konnte binnen Minuten in Eiseskälte umschlagen. Wer seinen Erwartungen nicht gerecht wurde, spürte das nicht nur beruflich, sondern persönlich. Ferrari vergab kaum zweite Chancen – nicht, weil er grausam war, sondern weil er von Menschen die gleiche Klarheit und Konsequenz erwartete, die er sich selbst abverlangte.

Gefangen im Mythos des eigenen Namens

Enzo Ferrari erschuf nicht nur eine Marke, sondern auch eine Erzählung über sich selbst, die bald größer wurde als jede einzelne seiner Taten. Der „Commendatore“, wie ihn alle nannten, wurde zur Projektionsfläche – für Stolz, Genialität, Eitelkeit, Melancholie. Und er wusste das. Er fütterte diesen Mythos, aber er war auch dessen Gefangener.

Er konnte nicht zurücktreten, nicht loslassen. Bis zu seinem Tod 1988 stand er an der Spitze seines Unternehmens – selbst als die Fiat-Gruppe längst eingestiegen war und Ferrari formal Teil eines Großkonzerns wurde. Entscheidungen, die ihn nicht betrafen, wurden verschoben oder ignoriert. Die letzte Instanz blieb er.

Diese Kontrolle machte ihn einsam. Ehemalige Vertraute berichteten von einem Enzo, der im Alter zunehmend in sich selbst gefangen war – umgeben von Erinnerungen, von Bildern verlorener Fahrer, von Auszeichnungen, die ihn nicht mehr berührten. Er sprach oft über die Vergangenheit – selten über die Zukunft.

Die Tragödie Dino Ferrari

Ein besonders tiefes Kapitel im Leben von Enzo Ferrari war der Tod seines Sohnes Alfredino („Dino“) Ferrari, der 1956 im Alter von nur 24 Jahren an einer Muskelerkrankung verstarb. Dino galt als begabt, feinfühlig, mit starkem technischem Verstand – und war designiert, eines Tages in die Fußstapfen seines Vaters zu treten.

Enzos Beziehung zu Dino war komplex – distanziert, aber voller Hoffnung. Der Tod seines Sohnes traf ihn wie ein Blitz. Zeitzeugen berichteten, dass Enzo monatelang verändert wirkte: verschlossener, schwermütiger, weniger kontrolliert. Noch Jahre später sprach er von Dino in fast religiöser Weise. Das erste Sechszylindermodell der Marke – der Dino 206 GT – wurde ihm gewidmet.

Doch auch hier zeigte sich der Widerspruch: Während er öffentlich Dinos Namen ehrte, tat er sich schwer damit, über seine Emotionen zu sprechen. Trauer wurde zum Ritual, nicht zur Öffnung. Und so blieb auch die Vaterrolle ein Schatten hinter dem Mythos.

Ein Italiener – und doch keiner wie die anderen

Enzo Ferrari war tief mit Italien verbunden, besonders mit Modena und Maranello. Und doch war er kein typischer Italiener. Er lebte einfach, trug meist einen dunklen Anzug, Sonnenbrille, ernste Miene. Er mochte keine Oper, kein Dolce Vita, keine oberflächliche Fröhlichkeit. Emotionen zeigte er in der Werkstatt – nie auf der Piazza.

Sein Italien war das Italien des Schweißes, der Werkzeuge, der Mechanik. Er glaubte an Arbeit, an Präzision, an Verantwortung. Und er verachtete jene, die diese Werte nur vorgaben.

Gleichzeitig war er stolz auf sein Land – aber er strebte nach internationaler Anerkennung. Ferrari sollte nicht nur in Italien glänzen, sondern auf der ganzen Welt bestehen. Und das tat es.

Ferrari – der Mann und der Mythos

Enzo Ferrari war kein einfacher Mensch. Er war ein Mann voller Widersprüche: leidenschaftlich und berechnend, stolz und verschlossen, visionär und konservativ. Er verlangte seinen Mitmenschen viel ab – aber sich selbst noch mehr. Und genau das machte ihn glaubwürdig.

Sein Unternehmen wurde zur Verlängerung seiner Persönlichkeit. Seine Autos wurden zu Boten einer Idee, die größer war als Technologie: der Idee, dass Maschinen Gefühle wecken können.

Wer heute einen Ferrari sieht, hört oder fährt, begegnet nicht nur einem Fahrzeug. Er begegnet einem Fragment des Enzo Ferrari, das bis heute in jedem Modell lebt – in der Linienführung, im Motorsound, im Emblem. Und genau deshalb bleibt Ferrari nicht nur eine Marke – sondern ein Enigma.

(in der Fortsetzung Teil 3 folgt:)

Kapitel 7: Der Mensch hinter dem Mythos – Enzos letzte Jahre

Kapitel 8: Die Formel-1-Ära – Lauda, Villeneuve und die goldenen Titeljahre

Kapitel 9: Nach dem Commendatore – Krise, Wandel und neue Helden

👉Was dir in Zusammenhang mit Ferrari auch gefallen könnte:

Enzo Ferrari – Der Mann, der den Mythos erschuf Teil 3 von 4:

Enzo Ferrari – Der Mann, der den Mythos erschuf Teil 4 von 4:

Investition in Hypercars – Wertsteigerung und Sammlerstrategien Teil 1 von 3