Enzo Ferrari – Der Mann, der den Mythos erschuf Teil 3 von 4:

Kapitel 7: Der Mensch hinter dem Mythos – Enzos letzte Jahre

In den letzten Jahrzehnten seines Lebens wandelte sich Enzo Ferrari vom Getriebenen zum Wächter. Der Mann, der einst selbst in der Boxengasse stand, Wagen skizzierte und Fahrer castete, zog sich allmählich aus dem operativen Tagesgeschäft zurück – zumindest scheinbar. Denn wer glaubte, Enzo würde die Kontrolle aus der Hand geben, unterschätzte ihn gewaltig. Tatsächlich wurde seine Präsenz in den 1970er- und 1980er-Jahren nur subtiler, nicht geringer. Ferrari wurde zum Phantom – allgegenwärtig, aber selten sichtbar. Und dennoch: Jede Entscheidung trug weiterhin seinen Stempel.

Diese Phase des Rückzugs war nicht nur altersbedingt. Sie war Ausdruck eines tieferliegenden Wandels: Ferrari wurde zur Weltmarke, die Rennsieger gebar, Mode inspirierte und Sammler faszinierte. Doch all das wuchs auf dem Fundament eines Mannes, der mehr denn je zum Symbol seines Unternehmens wurde. In dieser Zeit begann sich der Mythos Ferrari endgültig vom bloßen Automobilhersteller zur Idee Ferrari zu entwickeln – mit Enzo als lebendigem Denkmal im Zentrum.

Ein Leben im Schatten der eigenen Legende

Mit zunehmendem Alter veränderte sich Enzos öffentliches Auftreten. Seine legendären Sonnenbrillen wurden immer größer, sein Blick distanzierter, seine Worte bedachter. Er zeigte sich nur noch selten – meist beim Besuch befreundeter Journalisten, in schwarzweiß gehaltenen Interviews oder aus dem Fenster seines Büros in Maranello blickend.

Dabei war Enzo Ferrari nie der Typ für die große Bühne. Er hasste Preisverleihungen, mied Gesellschaftsempfänge und erschien nur selten zu internationalen Veranstaltungen. Doch in den letzten Jahren wurde seine Zurückhaltung zu einer bewussten Inszenierung der Abwesenheit. Sie nährte den Mythos – und schuf Raum für Spekulationen, Legenden, Heldenverehrung.

Ein stiller Beobachter mit scharfen Augen

Wer dachte, Enzo sei alt geworden und habe sich zurückgezogen, verwechselte Stille mit Schwäche. Selbst im hohen Alter las er täglich Dossiers, Rennberichte und technische Skizzen. Er führte Gespräche mit Ingenieuren – manchmal nur durch kurze Anmerkungen auf Notizzetteln oder über seine rechte Hand. Aber wenn er sprach, hatte jedes Wort Gewicht.

Er wusste, was in jedem Team vorging. Wer welche Leistung zeigte. Wer zweifelte. Wer flüsterte. Seine Mitarbeiter – selbst in der Spitze – beschrieben den Kontakt mit ihm als elektrisierend. Selbst junge Generationen, die ihn kaum persönlich kannten, fühlten seine Präsenz überall: in der Werkshalle, in der Motorabteilung, im Designbüro. Es war, als würde sein Schatten mitlesen, mitdenken, mitlenken.

Die letzte Generation seiner Fahrer

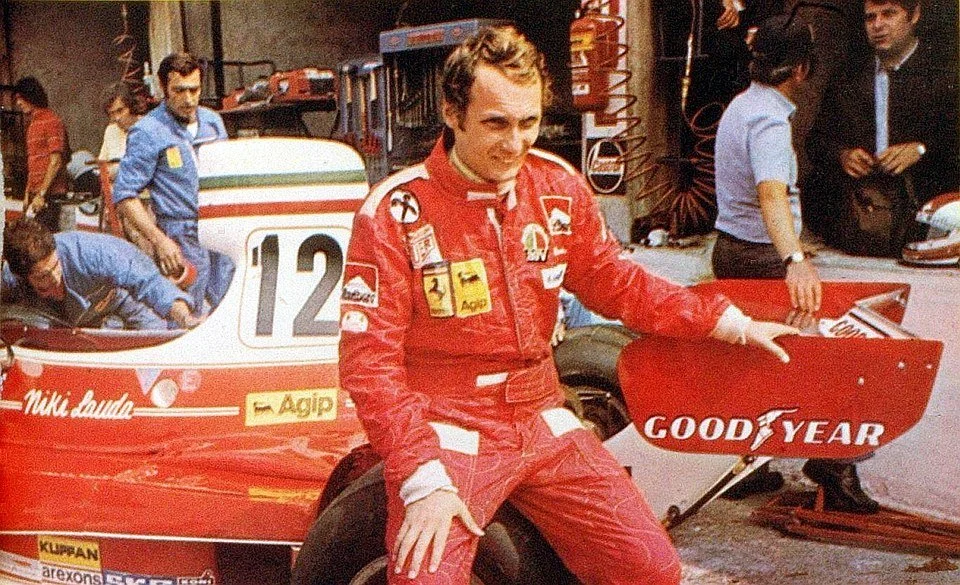

In den 1970er- und 1980er-Jahren prägten andere Namen das Ferrari-Cockpit: Clay Regazzoni, Niki Lauda, Gilles Villeneuve, Didier Pironi. Doch für Enzo war jeder von ihnen mehr als ein Angestellter. Sie waren die Gesichter seiner Idee – und zugleich potenzielle Verräter, wenn sie nicht funktionierten.

Mit Lauda verband ihn Respekt, mit Villeneuve fast schon väterliche Zuneigung. Doch selbst diese Nähe war stets eingebettet in ein strenges System aus Prüfung, Herausforderung und Distanz. Enzo testete jeden – nicht nur auf der Strecke, sondern auch auf Loyalität und Charakter.

Der Tod Villeneuves im Jahr 1982 traf ihn tief. Viele sagen, es sei der letzte Moment gewesen, in dem man Enzo Ferrari wirklich gebrochen sah. Er sprach danach selten über Gilles – aber wenn, dann in einer Art, wie man über einen verlorenen Sohn spricht.

Ein Mann, der wusste, wann es Zeit war, zu bleiben

Enzo Ferrari war kein Typ, der sich zur Ruhe setzen konnte. Obwohl die Welt um ihn herum sich wandelte, Ferrari an die Fiat-Gruppe angebunden wurde und neue Manager ihre Rollen übernahmen, blieb er im Zentrum – beratend, beobachtend, richtend.

Die Firmenstruktur wurde modernisiert. Prozesse professionalisiert. Doch nichts geschah ohne den Blick nach Maranello. Er war nicht mehr der aktive Lenker – aber er war immer noch das kulturelle Rückgrat, der Maßstab, der Mythos in Fleisch und Blut.

Der Tod und das Vermächtnis

Enzo Ferrari starb am 14. August 1988, im Alter von 90 Jahren, in Modena. Sein Tod wurde zunächst nicht öffentlich gemacht – auf seinen Wunsch hin. Erst zwei Tage später wurde die Nachricht verbreitet. Kein Pomp, keine Fernsehbilder, keine öffentliche Zeremonie. Ganz so, wie er gelebt hatte: diskret, stilvoll, unnahbar.

Doch die Welt hielt inne. Für einen Moment verstummten die Motoren. Zeitungen weltweit widmeten ihm Nachrufe, Formel-1-Teams fuhren mit Trauerbändern. Selbst Konkurrenten zollten Respekt. Denn unabhängig von der Marke war Enzo Ferrari eine Figur, die die Automobilwelt geprägt hatte wie kaum ein anderer.

Der Mensch hinter der Maschine

In seinen letzten Jahren wurde Enzo Ferrari mehr denn je zur Symbolfigur – eine lebende Brücke zwischen Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft. Er sprach wenig, aber er wirkte viel. Er war alt, aber seine Marke war jung. Und obwohl er sich zurückzog, blieb er das Zentrum eines Universums, das sich um ihn drehte.

Enzo Ferrari starb nicht einfach als Gründer eines Unternehmens. Er starb als Schöpfer eines Mythos, der bis heute auf der ganzen Welt lebt. Und der Mensch hinter diesem Mythos bleibt – bei aller Forschung, allen Zitaten und Anekdoten – bis heute ein Rätsel. Ein Enigma. Ein Ferrari.

7.1 Die 1970er: Rückzug ohne Loslassen

Die 1970er-Jahre markieren eine besondere Phase im Leben Enzo Ferraris. Sie gelten als das Jahrzehnt, in dem sich der Gründer zwar offiziell Schritt für Schritt aus der operativen Leitung seines Imperiums zurückzog – in Wahrheit aber blieb er weiterhin der unsichtbare Taktgeber im Hintergrund. Während sich die Welt veränderte, die Motorsport-Szene globaler und politischer wurde und Ferrari als Unternehmen neue Strukturen annahm, saß Enzo Ferrari weiterhin an seinem Schreibtisch in Maranello – als Hüter einer Idee, als letzte Instanz, als Mythos auf zwei Beinen.

Formelle Übergaben – informelle Macht

1971 trat Enzo Ferrari formal von der operativen Geschäftsleitung zurück. Die Verantwortung für das Tagesgeschäft übertrug er an eine neue, modernere Führungsstruktur – einschließlich technischer Direktoren und eines Verwaltungsrats. Die Fiat-Gruppe hatte bereits 1969 50 % der Ferrari-Anteile übernommen und drängte auf eine Professionalisierung des Unternehmens, besonders hinsichtlich Produktionsprozesse, Finanzen und Exportstrategie.

Doch wer glaubte, Ferrari würde sich damit zurücklehnen und anderen das Steuer überlassen, der irrte gewaltig. Die Übergabe war taktisch, nicht emotional. Enzo behielt das letzte Wort in den Dingen, die ihm wirklich wichtig waren: Motorsport, Designentscheidungen, Fahrerverträge – und das gesamte Auftreten der Marke. Fast nichts wurde beschlossen, ohne dass sein Büro konsultiert wurde.

„Ich habe die Pflicht abgegeben. Nicht die Verantwortung.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Ein Büro mit Durchgriff

Sein Büro in Maranello wurde in den 1970ern zur stillen Schaltzentrale. Besucher berichten, wie alles, was Rang und Namen hatte, irgendwann dort erscheinen musste – vom jungen Designer bis zum Formel-1-Fahrer. Die Regeln waren klar: Man sprach nur, wenn man gefragt wurde. Gespräche waren kurz, intensiv und nie beiläufig. Wer keine klare Haltung hatte, wurde ignoriert. Wer übertrieb, wurde aussortiert.

Ferrari war kein Kontrollfreak im operativen Detail – aber er war besessen von der Richtung. Seine Anmerkungen kamen oft in Form kurzer Sätze, Fragen oder Kommentare – aber jeder im Haus wusste: Ein Kopfnicken von Ferrari konnte ein Projekt zum Laufen bringen. Ein Stirnrunzeln konnte es beenden.

Eine neue Ära der Formel 1

Parallel zum strukturellen Wandel entwickelte sich in der Formel 1 eine neue Ära – technisch, medial und politisch. Die 1970er-Jahre brachten radikale Neuerungen: Slickreifen, Aerodynamik, Sponsoring-Deals und ein zunehmend globales Format. Der Sport wurde lauter, bunter – und gefährlicher.

Ferrari stand in dieser Zeit unter großem Druck. Nachdem die Marke in den 1960er-Jahren nicht konstant siegreich war, erwarteten Fans und Medien nun einen Wiederaufstieg. Die Verpflichtung von Niki Lauda 1974 markierte den Beginn dieser Renaissance. Unter technischer Leitung von Mauro Forghieri entwickelte das Team den legendären Ferrari 312T, mit dem Lauda 1975 den Weltmeistertitel holte – Ferraris erster Konstrukteurstitel seit über zehn Jahren.

Obwohl Enzo nicht mehr persönlich in der Boxengasse erschien, war seine Präsenz spürbar. Lauda selbst betonte, dass jede wichtige Entscheidung über seinen Vertrag, seine Technik oder seine Rennstrategie letztlich von Ferrari selbst abgenickt wurde – oft in knappen, aber präzisen Gesprächen. Enzo hatte die Fähigkeit, in wenigen Minuten die entscheidenden Punkte eines Problems zu erkennen – und zu entscheiden.

Eine stille Macht im Wandel der Zeit

Die Welt um Ferrari herum wandelte sich. Wirtschaftliche Unsicherheit, Ölkrise, neue Sicherheitsstandards, zunehmende Bürokratie – all das forderte Unternehmen heraus, sich zu modernisieren. Für Ferrari war das ein innerer Konflikt: Die Marke war tief in italienischer Handwerkskultur verwurzelt, aber sie musste nun international und industriell denken.

Ferrari selbst duldete diesen Wandel – aber stets mit Skepsis. Die fortschreitende Technologisierung, besonders in der Produktion, ließ ihn oft nostalgisch werden. Wo früher Hammer und Feile regierten, dominierten nun CAD-Zeichnungen, Prüflabore und Logistikketten. Für Enzo war das zwar unvermeidlich – aber nicht erstrebenswert.

Er hielt weiter an alten Tugenden fest: menschliches Talent, Erfahrung, Intuition. Maschinen waren ihm Werkzeuge, keine Orakel. Und moderne Managementmethoden betrachtete er mit Abstand. In seinem Herzen blieb er ein Mann aus Eisen und Öl – nicht aus Charts und KPIs.

Die Ferrari-Straßenfahrzeuge der 1970er

Auch bei den Straßenfahrzeugen war die Handschrift Enzo Ferraris weiterhin sichtbar. Modelle wie der Ferrari 365 GTB/4 „Daytona“, der 308 GTB oder der elegante Ferrari 400 entstanden unter seiner Ägide – wenn auch nicht mehr mit direkter Einmischung in jede technische Spezifikation.

Doch wichtige Entscheidungen – wie Designpartnerschaften mit Pininfarina, technische Grundsatzfragen oder die Ablehnung eines Vierzylinders – wurden weiterhin über seinen Tisch geleitet. Er behielt den Anspruch, dass jeder Ferrari – ob für Straße oder Rennstrecke – eine Seele haben müsse.

Die 1970er waren auch die Zeit, in der Ferrari begann, seine Modelle stärker als Luxusgüter zu positionieren. Der Kunde wurde selektiver ausgewählt, die Auslieferungen personalisierter, die Preise höher. Es war keine Massenmarke – es war eine Eintrittskarte in eine Legende.

Öffentlichkeit? Nur unter eigener Kontrolle

Enzo Ferrari zeigte sich in den 1970ern nur noch selten der Öffentlichkeit. Er gab kaum Interviews, mied Pressekonferenzen, erschien nicht bei offiziellen FIA-Veranstaltungen. Und wenn doch, dann stets kontrolliert – mit Sonnenbrille, schwarzem Anzug, kurzem Kommentar.

Diese bewusste Distanz war Teil seiner Strategie: Was man nicht vollständig sieht, bleibt faszinierend. Ferrari inszenierte sich selbst als Mythos – und die Welt spielte mit. Zeitungen nannten ihn „den Letzten der Titanen“, „den Diktator in Dunkelgrau“ oder schlicht „den Drachen von Maranello“. Enzo las diese Artikel – und lächelte. Denn er wusste: Wer über ihn spricht, stärkt den Mythos.

Rückzug? Ja. Aber nie Aufgabe.

Die 1970er-Jahre waren für Enzo Ferrari keine Phase der Schwäche, sondern eine Phase der Reifung und Reduktion. Er sprach weniger, erschien seltener – und prägte doch jede wichtige Entwicklung seiner Firma. Er ließ Veränderungen zu, wenn sie unvermeidlich waren. Aber er sorgte dafür, dass die Seele des Unternehmens nicht verwässert wurde.

Enzo Ferrari hatte sich zurückgezogen – aber nicht losgelassen. Er wurde zur lebenden Instanz, zur moralischen und kulturellen Mitte eines Unternehmens, das längst größer war als seine Person. Und dennoch: Solange er lebte, war kein Ferrari ein Ferrari ohne seinen Segen.

7.2 Der Tod von Dino und sein langes Echo

In der Geschichte von Enzo Ferrari gibt es viele dramatische Kapitel: legendäre Rennen, technische Meisterwerke, tragische Unfälle. Doch kein Ereignis hat ihn so tief geprägt wie der Tod seines Sohnes Alfredo „Dino“ Ferrari. Für den Mann, der als unnahbarer Patriarch galt, war dieser Verlust ein seelisches Erdbeben – und sein Echo hallte durch die Jahrzehnte seines Lebens und durch das gesamte Unternehmen.

Der Tod Dinos am 30. Juni 1956 war mehr als ein persönliches Drama. Er wurde zum Wendepunkt in Ferraris Innenleben, zum stillen Antrieb hinter vielen seiner späteren Entscheidungen – und zur Quelle eines Mythos, der das Unternehmen Ferrari emotional auflud wie kein zweiter Moment in seiner Geschichte.

Dino Ferrari – Der stille Erbe

Alfredo Ferrari, genannt Dino, wurde am 19. Januar 1932 geboren – als einziger ehelicher Sohn Enzo Ferraris mit seiner Frau Laura Dominica Garello. Bereits früh wurde klar: Dino war kein kräftiger Junge. Er war schmal, empfindsam, oft kränklich. Doch er war intelligent, höflich und technisch hochbegabt. Enzo erkannte in ihm ein außergewöhnliches Talent, vor allem für Maschinenbau und Motorenkonzepte.

Dino interessierte sich früh für Motorentechnik. Er studierte Maschinenbau an der Universität Bologna, später in Lausanne, und arbeitete ab 1954 in der Motorenentwicklung von Ferrari mit. Besonders intensiv beschäftigte er sich mit der Konzeption eines kleinen V6-Motors – ein für damalige Ferrari-Verhältnisse fast ketzerisches Projekt, da Enzo bekanntlich ein Verfechter der V12-Philosophie war.

Doch Dino überzeugte seinen Vater. Der V6 wurde zur Herzensangelegenheit – als ob der junge Mann ahnte, dass er wenig Zeit hatte, seine Vision zu verwirklichen.

Eine Krankheit, die nicht zu besiegen war

Schon im Jugendalter zeigte Dino erste Symptome einer degenerativen Erkrankung. Die Ärzte diagnostizierten später eine Muskeldystrophie vom Typ Duchenne – eine fortschreitende, unheilbare Erkrankung, bei der die Muskeln zunehmend schwinden. In den 1950er-Jahren bedeutete diese Diagnose einen unausweichlichen, langsamen Tod.

Die Krankheit schritt unerbittlich voran. Dino wurde schwächer, verlor an Gewicht, hatte Schwierigkeiten beim Gehen, später beim Atmen. Trotz seines körperlichen Verfalls arbeitete er bis zuletzt an Zeichnungen, Berechnungen und technischen Skizzen. In seinen letzten Monaten führte er Gespräche mit Chefingenieur Vittorio Jano – über den V6, über Kühlungsfragen, über Leistungsoptimierung.

Enzo war regelmäßig an seiner Seite, oft still, manchmal hilflos. Er sah seinen Sohn verblassen – und konnte nichts tun. Für einen Mann, der gewohnt war, alles zu kontrollieren, war das die ultimative Ohnmacht.

Bildquelle: Enzo (links) und Dino Ferrari (rechts) im Jahr 1955. Ein Jahr vor Dinos Tod. By Unknown photographer - [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=97826411

Der Tag, an dem etwas in Enzo starb

Dino starb am 30. Juni 1956 im Alter von nur 24 Jahren. Die Nachricht erschütterte das gesamte Werk in Maranello. Mitarbeiter beschrieben, wie Enzo nach dem Tod seines Sohnes für Tage nicht ansprechbar war. Es war einer der seltenen Momente, in denen er weinte – in aller Öffentlichkeit, ohne Scham.

„Mit Dino starb das letzte Stück von Enzo, das weich war.“

– Franco Gozzi, langjähriger Weggefährte

Von diesem Moment an wandelte sich Enzo Ferrari merklich. Er wurde noch verschlossener, distanzierter, fast kalt. Freunde berichteten, dass er nie wieder wirklich lachte. Er trug sein Leid wie einen Mantel – und sprach nur selten über seinen Sohn. Wenn doch, dann in leisen Worten, mit großer Präzision – als wolle er nichts beschönigen.

Der Dino lebt weiter – in Metall und Mythos

Doch Enzo Ferrari hatte eine besondere Art zu trauern: Er verwandelte Verlust in Symbolik. Wenige Jahre nach Dinos Tod präsentierte Ferrari ein neues Modell: den Dino 206 S, später gefolgt vom Dino 206 GT und 246 GT – die ersten Serienmodelle mit Mittelmotor und dem V6, den Dino einst mitkonzipiert hatte.

Die Marke „Dino“ wurde zu einem eigenen Sub-Label unterhalb der Ferrari-Hauptmarke. Enzo entschied sich bewusst dafür, den Namen „Ferrari“ nicht auf das Fahrzeug zu schreiben – als Zeichen der Demut, als stilles Denkmal an seinen Sohn. Die Fahrzeuge galten als emotionalste Modelle der Marke – elegant, leicht, fahraktiv, aber nicht aggressiv. Sie trugen etwas Zerbrechliches in sich – genau wie ihr Namensgeber.

Der V6-Motor, den Dino mitentworfen hatte, entwickelte sich zu einem Meisterwerk – kompakt, leistungsstark, flexibel. Er fand später auch in Formel-2-Wagen und sogar in Formel-1-Boliden Verwendung. Damit lebte Dino nicht nur als Name, sondern in der DNA der Marke Ferrari weiter.

Laura Ferrari – eine Frau am Rand

Ein oft übersehener Aspekt der Familiengeschichte ist die Rolle von Enzos Ehefrau Laura Ferrari. Ihre Beziehung war zeitlebens angespannt. Laura war temperamentvoll, misstrauisch, und oft eifersüchtig – insbesondere gegenüber Enzos enge Bindung zum Unternehmen und später zu ihrem Sohn.

Nach Dinos Tod verschärfte sich die Beziehung weiter. Laura soll mehrfach lautstarke Auseinandersetzungen mit Enzo gehabt haben – teils im Werk, teils privat. Einige Mitarbeiter berichteten, dass sie sich unkontrolliert in Unternehmensbelange einmischte und sogar technische Unterlagen durchsah. Enzo hielt sie zunehmend auf Distanz.

Der Tod ihres Sohnes belastete auch sie schwer. Doch statt in gemeinsamer Trauer zueinanderzufinden, entfernten sich die Eheleute. Enzo suchte Trost im Unternehmen – Laura in emotionaler Abgrenzung.

Ein innerer Bruch ohne Heilung

Dinos Tod wurde zum emotionalen Wendepunkt in Enzos Leben. Von da an sprach er in Interviews häufig über Vergänglichkeit, Zeit und Verantwortung. Er begann, sich stärker mit philosophischen Fragen auseinanderzusetzen. Doch echte Emotionen zeigte er kaum noch.

Er besuchte regelmäßig das Grab seines Sohnes – meist allein, oft spätabends. Kollegen berichteten, dass Enzo nach Arbeitsschluss manchmal in seinem Dienstwagen einfach losfuhr, um ungestört am Friedhof zu sitzen.

Er ließ sein Büro nach Dinos Tod nie umgestalten. Der Schreibtisch blieb der gleiche, der Stuhl an der gleichen Stelle. Auf seinem Schreibtisch stand immer ein Bild von Dino – eingerahmt, schlicht, präsent. Es war, als würde er niemals akzeptieren, dass sein Sohn nicht mehr Teil des täglichen Lebens war.

Die Wunde, die bleibt

Für Enzo Ferrari war der Tod von Dino kein abgeschlossenes Kapitel. Er war eine offene Wunde, die nie heilte – und die sein Handeln, Denken und Fühlen für den Rest seines Lebens prägte. Der Verlust machte ihn härter – und gleichzeitig verletzlicher. Er sprach seltener, entschied kompromissloser und ließ niemanden mehr so nah an sich heran wie seinen Sohn.

Doch gerade diese Trauer, dieses bleibende Echo der Liebe und des Verlustes, formten den Menschen hinter dem Mythos. Es war Dinos Tod, der Enzo Ferrari zu dem machte, was er in seinen letzten Jahrzehnten war: ein Mensch zwischen Genie und Schmerz, zwischen Weltfirma und Grabstein – unsterblich durch das, was er erschuf, aber zutiefst menschlich durch das, was er verlor.

7.3 Die Beziehung zu Lauda, Villeneuve und Pironi

In kaum einem anderen Bereich wurde Enzo Ferraris zwiespältige Persönlichkeit so deutlich wie in seiner Beziehung zu seinen Rennfahrern. Für ihn waren sie die Speerspitze der Marke, Krieger im roten Kampfanzug, Soldaten des Mythos – aber niemals Freunde. Die Bindung zwischen Ferrari und seinen Piloten war von Anfang an geprägt durch Leistung, Loyalität, Kontrolle – und Distanz.

Doch es gab Ausnahmen. In den 1970er- und frühen 1980er-Jahren traten drei Männer in sein Leben, die ihn auf unterschiedliche Weise berührten: Niki Lauda, Gilles Villeneuve und Didier Pironi. Jeder von ihnen wurde zu einer Projektionsfläche für Ferraris Ideale – und zugleich zu einem Spiegel seiner innersten Widersprüche.

Niki Lauda – der Rationalist, dem er vertraute

Als Niki Lauda 1974 bei Ferrari anheuerte, war das Werkteam in der Formel 1 auf der Suche nach einem Neuanfang. Es war Luca di Montezemolo – Enzos Assistent und rechte Hand –, der den jungen, unbekannten Österreicher empfahl. Enzo war zunächst skeptisch. Ein kühler, rechnender Fahrer, ohne italienisches Temperament? Doch Lauda überzeugte auf seine Weise: nicht durch Charme, sondern durch Leistung und Präzision.

Die Beziehung zwischen Ferrari und Lauda war professionell – aber von Respekt geprägt. Lauda, selbstbewusst und analytisch, gewann Enzos Vertrauen, indem er nicht um Nähe bat, sondern durch Ergebnisse sprach. Schon 1975 holte er den ersten WM-Titel für Ferrari seit über zehn Jahren. Ferrari war beeindruckt von Laudas Klarheit, seiner Arbeitsmoral und seinem Fokus. Er sagte später:

„Lauda war kein Fahrer, der mir gefallen wollte. Er wollte nur gewinnen. Und das reichte mir.“

Die Beziehung war nicht herzlich, aber stabil. Bis zum Unfall am Nürburgring 1976. Lauda verunglückte schwer, lag im Koma, wurde notoperiert – und kehrte nach nur sechs Wochen wieder ins Cockpit zurück. Enzo Ferrari ließ in dieser Phase medizinische Gutachten einholen, schickte persönliche Ärzte und ließ den Wagen für Lauda umrüsten – eine seltene Geste der Fürsorge, die zeigte, wie sehr er Lauda schätzte.

Doch die Beziehung zerbrach 1977 – nicht am Unfall, sondern am Management. Lauda fühlte sich politisch untergraben, von der Teamführung vernachlässigt. Enzo selbst hielt sich aus dem Konflikt heraus – eine Entscheidung, die Lauda als Enttäuschung empfand. Nach seinem zweiten Titel verließ er Ferrari. Später sagte er: „Ich habe ihn respektiert. Aber ich wusste: Ich bin für ihn nur so lange wertvoll, wie ich funktioniere.“

Gilles Villeneuve – der geliebte Sohn, den er verlor

Wenn es je einen Fahrer gab, zu dem Enzo Ferrari eine echte emotionale Bindung hatte, dann war es Gilles Villeneuve. Der junge Kanadier trat 1977 ins Team ein – klein, schmächtig, fast schüchtern. Doch auf der Strecke war er ein Berserker: mutig, wild, leidenschaftlich bis zur Selbstaufgabe.

Ferrari war fasziniert. Gilles verkörperte das, was er bei vielen anderen vermisste: bedingungslosen Einsatz. Der Commendatore sagte über ihn:

„Er hatte das Herz eines Löwen und die Seele eines Kindes.“

Villeneuve fuhr mit einer Mischung aus Wahnsinn und Präzision, die Enzo an die Helden der Vorkriegszeit erinnerte. Er war bereit, alles zu geben – auch sein Leben. Und Ferrari, der selten Gefühle zeigte, sprach über Gilles wie über einen zweiten Sohn. Es war die erste und einzige Fahrerpaarung, bei der Enzo öffentlich sagte, er empfinde „Zuneigung“.

Doch diese Zuneigung wurde zur Tragödie. Am 8. Mai 1982 verunglückte Villeneuve im Qualifying zum GP von Zolder tödlich – mit über 250 km/h. Das ganze Fahrerlager erstarrte. Enzo Ferrari, inzwischen 84 Jahre alt, wurde bei der Nachricht bleich und sprachlos. Er erschien nicht zur Beerdigung – eine Geste, die viele missverstanden. Doch er sagte später:

„Ich wollte ihn nicht tot sehen. Ich wollte ihn so in Erinnerung behalten, wie er fuhr – mit fliegenden Rädern und glühendem Blick.“

Nach Gilles’ Tod ließ Enzo ein Denkmal in Maranello errichten. Sein Büro wurde mit einem Porträt von Villeneuve geschmückt. Bis zu seinem Tod sprach er von ihm in der Vergangenheitsform, aber mit Gegenwartsgefühl – als sei er nie wirklich gegangen.

Didier Pironi – der tragische Vertrauensbruch

Die Beziehung zu Didier Pironi war das genaue Gegenteil der zu Villeneuve: Sie begann professionell, gewann an Tiefe – und endete in Enttäuschung, Misstrauen und Tragödie. Pironi trat 1981 ins Ferrari-Team ein und war schnell, intelligent, strategisch. Ferrari sah in ihm einen künftigen Weltmeister.

Doch die fatale Wendung kam am 25. April 1982 in Imola: Beim Großen Preis von San Marino lag Villeneuve vor Pironi – ein teaminterner Deal sollte beide auf Positionen 1 und 2 bringen. Doch Pironi überholte Villeneuve in der letzten Runde – gegen die Absprache. Gilles war außer sich, fühlte sich verraten. Zwei Wochen später verunglückte er in Zolder – viele glauben, auf der Suche nach einer schnellen Runde, um Pironi zu demütigen.

Der Bruch zwischen Enzo Ferrari und Didier Pironi war tief. Enzo, der Pironi zuvor geschätzt hatte, sprach ab diesem Moment nur noch selten mit ihm. Er sah in ihm nicht den Mörder seines Lieblingsfahrers – aber einen, der den Ehrenkodex gebrochen hatte. Für Enzo, den Moralist im Hintergrund, war das schlimmer als ein Regelverstoß.

Pironi verunglückte wenig später selbst schwer – bei Tests in Hockenheim. Seine Karriere war beendet. Enzo sprach nie wieder offen über ihn.

Enzos Fahrervorstellungen – zwischen Ideal und Realität

Diese drei Fahrer – Lauda, Villeneuve, Pironi – zeigen, wie unterschiedlich Enzo Ferrari seine Piloten wahrnahm:

Lauda war der disziplinierte Profi, dem er vertraute, aber nie wirklich nahe kam.

Villeneuve war der leidenschaftliche Kämpfer, dem er emotional verfiel – und dessen Tod ihn erschütterte.

Pironi war der Strategische, der ihn enttäuschte – weil er ihn menschlich falsch eingeschätzt hatte.

Was sie vereinte: Alle wurden nicht nur technisch, sondern auch moralisch gemessen. Für Enzo zählten Charakter, Aufopferung, Treue. Wer nur schnell war, aber berechnend – war ihm suspekt. Wer riskierte, verlor, aber mit Herz kämpfte – konnte sein Vertrauen gewinnen.

Helden unter Beobachtung

Für Enzo Ferrari waren Rennfahrer keine Stars. Sie waren Spiegel seiner Ideale – oder Mahnmale seiner Verluste. In ihnen suchte er den Beweis, dass Mut, Talent und Ehre nicht ausgestorben waren. Doch er wusste auch: Wer hoch fliegt, fällt tief. Und wer zu nah kommt, kann verletzen.

Die Geschichten von Lauda, Villeneuve und Pironi erzählen deshalb nicht nur vom Motorsport. Sie erzählen von einem Mann, der Größe erkannte, aber Nähe fürchtete. Der bewunderte, aber nicht verzieh. Und der in jedem Fahrer einen Teil seiner eigenen Geschichte wiederfand – zwischen Sieg, Stolz und Schmerz.

7.4 Enzo Ferrari privat – der verschlossene Visionär

Enzo Ferrari war eine der bekanntesten Persönlichkeiten Italiens im 20. Jahrhundert – und zugleich eine der unzugänglichsten. Trotz (oder gerade wegen) seiner immensen Präsenz im Motorsport und seiner Rolle als Vater der Scuderia Ferrari, war sein Privatleben stets von einem Schleier aus Schweigen, Distanz und Widersprüchen umgeben. Wer war dieser Mann wirklich, wenn die Boxentore sich schlossen, wenn die Motoren schwiegen?

Dieses Kapitel nähert sich einem Menschen, der viel gesehen, viel erschaffen und viel verloren hat – aber nur wenig von sich preisgab. Ein Mann, der als Visionär galt, aber im Alltag von klaren Ritualen, Routinen und innerer Abgrenzung lebte. Der Öffentlichkeit inszenierte er einen Mythos. Für sich selbst baute er eine Schutzhülle aus Schweigen und Struktur.

Der Tagesablauf eines Patriarchen

Enzo Ferrari war ein Mann der Gewohnheit – fast besessen von Routinen. Er stand früh auf, las die Zeitung mit Akribie – meist mehrere Blätter, sowohl lokale als auch nationale –, und ging dann ins Werk in Maranello. Er hatte seinen eigenen Eingang, seine eigene Route durch die Gebäude, sein Büro – schlicht eingerichtet, aber voller Symbolkraft.

Er sprach nicht viel, aber alles wurde registriert. Wer ihm begegnete, wurde mit einem kurzen Nicken bedacht – oder ignoriert. Wer in sein Büro gebeten wurde, wusste, dass es wichtig war. Die Gespräche waren nie lang, nie beiläufig. Und immer war Ferrari derjenige, der entschied, wann sie endeten.

Er verließ das Werk meist am Nachmittag, aß im kleinen Kreis – oft alleine oder mit wenigen vertrauten Kollegen – und kehrte am Abend zurück in sein Wohnhaus in Modena. Dort verbrachte er Zeit mit sich selbst, mit Briefen, technischen Berichten, und gelegentlich mit Fernsehsendungen über Sport oder Politik. Er lebte zurückgezogen, aber nie in Untätigkeit. Sein Leben war durchgetaktet – wie ein Motor, der im Leerlauf nie abschaltet.

Ein Mann der Isolation

Enzo Ferrari mied große Menschenansammlungen, Empfänge oder offizielle Anlässe. Selbst in Italien, wo Repräsentation oft Teil des Erfolgs ist, zeigte er sich nur selten in der Öffentlichkeit. Er erschien nie bei Formel-1-Rennen außerhalb Italiens. Bei Ferrari-Veranstaltungen war er meist abseits, in einem separaten Raum, von dem aus er alles beobachten konnte – aber ohne direkt teilzunehmen.

Diese Selbstisolierung war kein Zufall. Enzo suchte Distanz – vielleicht aus Kontrolle, vielleicht aus Angst vor Verletzlichkeit. Er wollte niemandem zu nahe kommen, wollte nicht der Mann sein, den man umarmt, feiert oder tröstet. Viele Kollegen, die jahrzehntelang mit ihm arbeiteten, sagten, sie hätten ihn nie privat besucht, nie mit ihm gelacht, nie ungezwungen gesprochen.

Und doch war er kein kalter Mensch. In seltenen Momenten zeigte er Anteilnahme – etwa nach dem Tod eines Fahrers oder beim Besuch eines kranken Mitarbeiters. Aber diese Gesten blieben leise, fast verborgen. Emotion ja – aber nie öffentlich.

Die Beziehung zu Frauen – verschlossen und widersprüchlich

Enzos Ehe mit Laura Dominica Garello Ferrari war von Spannungen geprägt. Laura war temperamentvoll, eifersüchtig und fühlte sich häufig ausgeschlossen – besonders, weil Enzo mehr Zeit in Maranello verbrachte als mit ihr. Nach dem Tod ihres Sohnes Dino verschlechterte sich das Verhältnis deutlich. Es kam zu lautstarken Auseinandersetzungen, sogar innerhalb des Werks. Viele Mitarbeiter empfanden Laura als unberechenbar, und Enzo schützte sich, indem er sie aus dem operativen Geschehen ausschloss.

Parallel dazu unterhielt Enzo eine langjährige Beziehung mit einer anderen Frau: Lina Lardi. Aus dieser Verbindung ging ein weiterer Sohn hervor – Piero Ferrari, geboren 1945, der erst Jahrzehnte später offiziell den Namen Ferrari tragen durfte. Enzo kümmerte sich um Lina und Piero, hielt die Beziehung jedoch zeitlebens im Hintergrund. Für einen katholischen Italiener dieser Zeit war das ein heikler Balanceakt – gesellschaftlich, familiär, persönlich.

Diese Konstellation zeigt viel von Ferraris innerer Welt: Er konnte Gefühle haben, aber nicht leben. Er organisierte seine Beziehungen wie sein Unternehmen – kontrolliert, strukturiert, mit Sicherheitsabstand.

Der Blick in den Spiegel – Selbstbild und Zweifel

Obwohl Enzo Ferrari nach außen hin kontrolliert und überlebensgroß wirkte, war er sich seiner eigenen Widersprüche bewusst. In seltenen Interviews sprach er über Themen wie Alter, Verantwortung und Einsamkeit – immer mit der Melancholie eines Mannes, der viel erreicht, aber auch viel verloren hatte.

„Ich bin ein Mensch mit vielen Schatten. Ich habe Autos gebaut, um vor mir selbst davonzufahren.“

– Enzo Ferrari

Er litt unter dem Tod seines Sohnes Dino, unter dem Verlust vieler Fahrer, unter dem Druck, ständig perfekt sein zu müssen. Doch er ließ sich nie helfen, nie therapieren. Seine Verarbeitung geschah durch Arbeit, Disziplin und Reduktion. Wer ihn fragte, ob er glücklich sei, bekam meist keine Antwort – oder ein Achselzucken.

Glaube, Philosophie und Vergänglichkeit

Enzo Ferrari war kein besonders religiöser Mensch – zumindest nicht im traditionellen Sinn. Er glaubte an Prinzipien, an Ethik, an Leistung. Aber er sprach selten über Gott, Kirche oder Jenseits. Und doch beschäftigte ihn die Frage der Vergänglichkeit tief.

In späteren Jahren besuchte er regelmäßig das Grab seines Sohnes, sprach mit Geistlichen, führte Gespräche über Verantwortung, Schuld und Nachruhm. Er wusste, dass er etwas geschaffen hatte, das größer war als er selbst – aber er wusste auch, dass er dafür einen hohen Preis gezahlt hatte: emotional, familiär, menschlich.

Sein Lebensmotto blieb ambivalent: „Ich wollte nie ein erfolgreicher Mann sein. Ich wollte ein Mann sein, der nicht vergessen wird.“

Der private Ferrari bleibt ein Rätsel

Enzo Ferrari war in der Öffentlichkeit eine Machtfigur – streng, kontrolliert, unerbittlich. Privat war er ein Mensch im Rückzug, geprägt von Verlusten, innerer Disziplin und einer fast stoischen Melancholie. Er war kein Genie im klassischen Sinn, sondern ein Mann mit unerschütterlichem Willen und tief verwurzeltem Schmerz.

Man kann ihn nicht wirklich „kennenlernen“. Zu viele Seiten blieben bewusst im Dunkeln. Aber genau diese Mischung aus Nähe und Distanz, aus Stärke und Verletzlichkeit macht ihn bis heute so faszinierend. Enzo Ferrari war kein Mann, den man umarmte. Aber er war einer, den man ehrfürchtig betrachtete – wie ein Denkmal, das lebt.

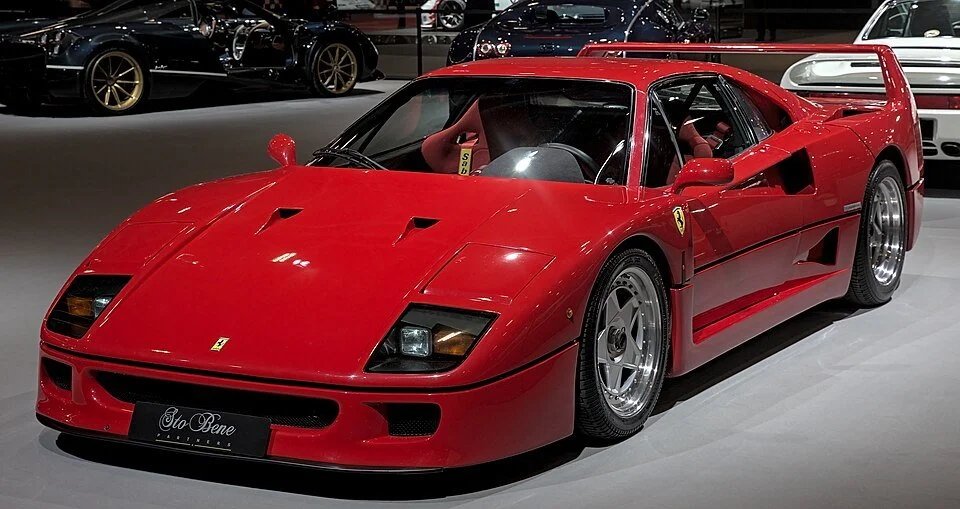

7.5 – 1988: Der letzte Ferrari mit Enzos Segen

Der Sommer 1988 markiert das Ende einer Ära – nicht nur für Ferrari, sondern für die ganze Welt des Motorsports. Enzo Ferrari, der fast sieben Jahrzehnte lang erst als Fahrer, dann als Teamchef, später als Patriarch eine gesamte Branche geprägt hatte, erlebte seine letzten Wochen in stiller Wachsamkeit. Er wusste, dass seine Zeit gekommen war. Doch bis zuletzt blieb er, was er immer gewesen war: der wachsame Hüter seiner Idee.

In diesen Monaten begleitete er noch ein letztes Projekt – das, was viele als „den letzten echten Ferrari“ bezeichnen: den Ferrari F40. Kein anderes Modell verkörperte seine Philosophie in ihrer Reinform so kompromisslos wie dieses Auto. Als das Auto vorgestellt wurde, war der Commendatore bereits körperlich geschwächt – doch sein Geist war in jedem Bolzen spürbar.

Der F40 – Ferraris letztes Vermächtnis

Der Ferrari F40 wurde 1987 zum 40-jährigen Jubiläum des Unternehmens präsentiert – und sofort zur Legende. Es war ein Supersportwagen ohne Schnörkel, ohne Kompromisse, ohne Rücksicht auf Komfort. Keine Servolenkung, kein ABS, keine elektrische Helferlein. Nur Kohlefaser, Turbo-Power und das pure Versprechen von Geschwindigkeit.

Ferrari wollte mit dem F40 nicht einfach ein Auto bauen – sondern ein Statement. Ein Gegenentwurf zur zunehmenden Digitalisierung und Bequemlichkeit der Automobilwelt. Der F40 war roh, direkt, brutal schön. Genau das mochte Enzo. Er sagte in einem seiner letzten Interviews:

„Der F40 ist das, was ich für richtig halte. Ohne unnötigen Luxus. Ein Auto für den Fahrer, nicht für den Besitzer.“

Das Design stammte – wie so oft – von Pininfarina, unter der Leitung von Leonardo Fioravanti. Unter der Haube arbeitete ein 2,9-Liter-V8-Biturbo mit 478 PS. Der Wagen wog kaum über 1.100 Kilo. Die Fahrwerte waren atemberaubend: 0–100 km/h in unter 4 Sekunden, über 320 km/h Höchstgeschwindigkeit. Doch Zahlen waren nicht das Entscheidende.

Der F40 war das destillierte Ferrari-Gefühl. Er brüllte, zerrte, biss – und belohnte den, der ihn verstand.

Ein letzter stiller Sommer

Während der F40 durch Presse, Messen und Testfahrten zum Mythos wurde, zog sich Enzo Ferrari in den letzten Monaten seines Lebens weiter zurück. Er lebte in seinem Haus in Modena, kam nur noch selten ins Werk, empfing aber weiterhin Besucher – Journalisten, Freunde, Fiat-Manager.

Seine Gesundheit war angeschlagen. Die Augen schwächer, die Stimme leiser. Doch sein Verstand blieb messerscharf. Noch im Frühjahr 1988 soll er technische Unterlagen zum F40 geprüft, Rückfragen zu Materialien gestellt und sogar Kommentare zu Testberichten verfasst haben. Es war, als wolle er das letzte Kapitel selbst mit Handschrift beenden.

Im Juli 1988 fuhr ein F40 – mit Sonderlackierung – durch die Tore von Maranello, direkt in den Innenhof. Enzo Ferrari stand am Fenster seines Büros. Er beobachtete das Auto lange – ohne Worte. Später soll er zu einem Mitarbeiter gesagt haben: „Er ist wild. Gut so.“

14. August 1988 – Der Tod des Commendatore

Am 14. August 1988 starb Enzo Ferrari im Alter von 90 Jahren. Es war ein Sonntagmorgen. Keine dramatische Szene, keine intensive mediale Begleitung. Er war friedlich eingeschlafen – in seinem Haus, in seiner Stadt, in seiner Welt.

Auf seinen Wunsch hin wurde sein Tod zwei Tage lang nicht bekanntgegeben. Die Öffentlichkeit erfuhr erst am 16. August davon – ein letzter Akt der Kontrolle, ein letztes Signal an die Welt: Ich gehe, aber ich bestimme den Zeitpunkt.

Italien stand still. Die Zeitungen trugen schwarze Titelseiten, die Fernsehprogramme unterbrachen ihre Sendungen. In Maranello weinten Arbeiter, Mechaniker, Ingenieure. Selbst Konkurrenten wie Porsche, Mercedes oder McLaren zollten Respekt.

„Ferrari ist nicht tot. Er hat sich nur entschlossen, nicht mehr sichtbar zu sein.“

– Ehemaliger Ferrari-Techniker

Ein epischer Moment in Monza

Nur wenige Wochen nach seinem Tod fuhr Ferrari beim Großen Preis von Italien in Monza einen Doppelsieg ein. Gerhard Berger und Michele Alboreto belegten Platz 1 und 2 – in einer Saison, die bis dahin vom dominanten McLaren-Team (mit Ayrton Senna und Alain Prost) beherrscht worden war.

Es war der einzige Sieg Ferraris im Jahr 1988. Und er kam ausgerechnet auf heiligem Boden, in Monza, nur Tage nach dem Tod des Gründers. Das Publikum tobte, Tränen flossen, Ferrari-Flaggen wehten. Für viele Fans war es kein Zufall. Es war ein Gruß von oben – Enzos letzter Blick auf „seine“ Strecke.

Noch heute gilt dieser Sieg als einer der emotionalsten Momente der Formel-1-Geschichte. Die Mechaniker trugen schwarze Armbinden. Auf dem Wagen: ein kleiner, schwarzer Aufkleber – „In Memoriam E.F.“

Was bleibt: Mehr als ein Name

Der Ferrari F40 war das letzte Modell, das Enzo Ferrari persönlich absegnete. Danach begannen neue Kapitel: neue Generationen, neue Technologien, neue Strategien. Doch kein Auto, kein Vorstand, kein Fahrer konnte je den Platz einnehmen, den Enzo Ferrari in diesem Unternehmen hatte.

Er war mehr als Gründer. Er war das Gewissen, das Gefühl, das Fundament. Sein Einfluss lebt weiter – in jeder Linie eines Ferrari, im Sound der Motoren, im Mythos der Scuderia. Sein Name ist auf jedem Modell – aber seine Seele ist in der Haltung geblieben.

Bis heute werden neue Modelle an seinem Maßstab gemessen. Bis heute zitiert man seine Prinzipien, seine Sprüche, seine Philosophie. Kein anderer Mensch hat es geschafft, ein Unternehmen so sehr mit seiner Persönlichkeit zu durchdringen – und gleichzeitig im Schatten zu bleiben.

Der letzte Gruß eines Giganten

Der F40 war nicht nur ein Auto. Er war ein Abschiedsbrief in Kohlefaser und Feuer. Er war ein letztes „Grazie“ an die Geschwindigkeit, an den Mut, an die Leidenschaft – und an die Welt, die Enzo Ferrari mitgeformt hat.

Als der Wagen vorgestellt wurde, war Ferrari bereits gezeichnet von Alter und Krankheit. Doch er wusste: Dieser Wagen war sein Vermächtnis. Kein Kompromiss. Kein Luxus. Nur das, was zählt: Herz, Maschine, Mythos.

Und so war sein Tod kein Abbruch – sondern ein Vollendungspunkt. Nicht als Schluss, sondern als Übergang. Enzo Ferrari verließ die Bühne, auf der er nie stehen wollte – und überließ sie dem Echo seiner Motoren.

Kapitel 8: Die Formel-1-Ära – Lauda, Villeneuve und die goldenen Titeljahre

Ferrari und die Formel 1 – diese Verbindung ist mehr als nur sportlich. Sie ist symbolisch, geschichtsträchtig und emotional aufgeladen wie kaum ein anderes Kapitel im Motorsport. Seit dem allerersten Formel-1-Rennen 1950 war Ferrari dabei. Und obwohl der Weg oft steinig war, wurde die Scuderia zur erfolgreichsten und bekanntesten Rennmannschaft der Welt.

Doch der Weg zum Mythos war nicht geradlinig. Zwischen Höhenflügen und Krisen, Tragödien und Triumphen entwickelte sich eine Erzählung, in der große Namen wie Niki Lauda, Gilles Villeneuve, Michael Schumacher und Jean Todt zentrale Rollen spielen. Die Formel-1-Geschichte Ferraris ist die Geschichte von Technik, Politik, Stolz – und von einem Team, das oft gegen sich selbst kämpfte, bevor es die Welt besiegen konnte.

8.1 – Der Wiederaufstieg mit Lauda (1974–1977)

Nach einer schwierigen Phase in den späten 1960er- und frühen 1970er-Jahren steckte Ferrari in einer sportlichen und organisatorischen Krise. Die Formel 1 war im Umbruch: neue Technik, neue Stars, neue Teams. Während Lotus, McLaren und später Tyrrell die Szene bestimmten, war Ferrari unbeständig, politisch zerrissen und technisch überholt. Der Mythos lebte – doch der Erfolg blieb aus. Was es brauchte, war nicht nur ein schneller Fahrer, sondern eine Neuausrichtung in Geist und Struktur.

Die Antwort kam in Form eines jungen Österreichers mit außergewöhnlicher Disziplin, analytischem Denken und einem unbestechlichen Charakter: Niki Lauda.

Die Vorarbeit: Montezemolo und Regazzoni

Bevor Lauda kam, hatte Ferrari bereits begonnen, die Weichen neu zu stellen. 1974 wurde Luca di Montezemolo zum Teamchef der Scuderia ernannt. Der junge, smarte Jurist war ein enger Vertrauter Enzo Ferraris und sollte frischen Wind in das marode Team bringen.

Montezemolo brachte Clay Regazzoni zurück ins Team – einen soliden, schnellen Piloten, der Ferrari gut kannte. Doch der eigentliche Coup war Lauda, damals ein weitgehend unbekannter Fahrer bei BRM, den Montezemolo in dessen Debütsaison beobachtet hatte. Er überzeugte Enzo, Lauda zu holen – ein strategischer Glücksgriff.

Niki Lauda – kein typischer Ferrari-Fahrer

Lauda war nicht der Typus Fahrer, den Ferrari bis dahin bevorzugt hatte. Er war kühl, kalkulierend, rational. Kein Latin Lover, kein Draufgänger, kein Showman. Doch gerade deshalb war er für die strukturell angeschlagene Scuderia genau der Richtige. Lauda brachte Ordnung in das Chaos. Er verlangte technische Exaktheit, kontinuierliche Weiterentwicklung und klare Kommunikation – Tugenden, die bei Ferrari nicht selbstverständlich waren.

Schon in seiner ersten Saison 1974 holte Lauda zwei Siege und mehrere Pole Positions. Die technische Zusammenarbeit mit Chefingenieur Mauro Forghieri war fruchtbar, offen, fordernd – und produktiv. Lauda brachte ein System, das funktionierte. Und Ferrari begann zu liefern.

1975 – Die Rückkehr an die Spitze

Bereits 1975 war der Durchbruch geschafft. Lauda gewann fünf Rennen, dominierte über weite Strecken die Saison und sicherte sich den Fahrerweltmeistertitel. Ferrari gewann auch die Konstrukteurswertung – der erste Titelgewinn für das Team seit 1964.

Das Auto, der Ferrari 312T, war ein Meilenstein: stabil, aerodynamisch effizient, kraftvoll. Doch der Schlüssel zum Erfolg lag nicht im Motor oder im Chassis – sondern in der Symbiose zwischen Fahrer und Team. Lauda testete, analysierte, forderte – und Ferrari lieferte. Es war ein neues Ferrari, nüchterner, effizienter, professioneller.

Enzo Ferrari war stolz – und dankbar. Obwohl er selten lobte, schrieb er Lauda in einem Brief:

„Sie haben nicht nur Rennen gewonnen. Sie haben unsere Seele neu geordnet.“

1976 – Triumph, Tragödie und Charakter

1976 sollte zum Schicksalsjahr werden. Lauda begann die Saison dominierend, gewann vier der ersten sechs Rennen. Alles sprach für eine Titelverteidigung – bis zum 1. August 1976, beim Großen Preis von Deutschland auf dem Nürburgring.

Lauda verunglückte schwer. Sein Ferrari prallte in eine Leitplanke, fing Feuer, Lauda wurde schwer verletzt – Verbrennungen, Rauchvergiftung, Koma. Die Welt hielt den Atem an. Doch was folgte, war eine der größten Comeback-Geschichten der Sportgeschichte.

Nur 42 Tage nach dem Unfall saß Lauda wieder im Ferrari – in Monza. Noch geschwächt, mit frischen Wunden und Angst im Blick – aber mit dem Willen eines Champions. Er wurde Vierter. Und Ferrari feierte ihn wie einen Sieger.

Doch der Titel war verloren. In einem regnerischen Saisonfinale in Fuji stieg Lauda aus – aus Sicherheitsbedenken. Der Titel ging an James Hunt. Ferrari respektierte die Entscheidung – Enzo selbst sagte:

„Er hat mehr Mut gezeigt, als ein Sieg je bedeuten könnte.“

1977 – Ein letzter Titel und das bittere Ende

1977 wurde Lauda erneut Weltmeister – trotz innerer Spannungen im Team. Enzo Ferrari hatte nach Laudas Unfall Carlos Reutemann ins Team geholt, was Lauda als Vertrauensbruch empfand. Er fühlte sich nicht mehr unterstützt, sondern geprüft. Der alte Ferrari-Stolz, der emotionale Stolz, war zurück – und kollidierte mit Laudas sachlichem Systemdenken.

Nach dem Titel kündigte Lauda seinen Abschied. Das Ende war leise, aber kühl. Er verließ Ferrari mit zwei Weltmeistertiteln – und dem tiefen Respekt eines Teams, das durch ihn wieder gelernt hatte zu gewinnen.

Der Wiederaufstieg durch Disziplin

Niki Lauda war kein Ferrari im klassischen Sinn. Doch gerade deshalb war er der perfekte Mann zur richtigen Zeit. Er führte Ferrari aus der Krise, lehrte das Team Struktur, Präzision und Geduld – und wurde zum Motor eines neuen Selbstverständnisses.

Sein Einfluss reichte weit über seine Rennsiege hinaus. Lauda war nicht nur Fahrer – er war Systemerneuerer. Und genau das machte ihn zu einem der bedeutendsten Menschen in der Geschichte der Scuderia.

8.2 – Villeneuve: Der Ritter auf vier Rädern

Gilles Villeneuve war kein gewöhnlicher Rennfahrer – er war ein Phänomen. Klein, drahtig, höflich, fast schüchtern im Umgang – doch sobald er das Cockpit betrat, wurde er zur Urgewalt. Für Enzo Ferrari war er nicht nur ein Fahrer, sondern ein Ideal. Villeneuve verkörperte das, was Enzo immer suchte, aber selten fand: kompromisslosen Mut, absolute Hingabe und eine tiefe Verbindung zum Auto.

Ein stiller Beginn, ein lauter Auftritt

Gilles Villeneuve wurde 1977 entdeckt, als er mit einem McLaren beim Großen Preis von Großbritannien debütierte. Enzo Ferrari war sofort fasziniert – weniger von den Rundenzeiten als von Villeneuves kompromissloser Herangehensweise. Noch im selben Jahr holte Ferrari ihn ins Team, zunächst als Ersatz für Niki Lauda, der Ferrari im Streit verließ.

Viele Experten waren skeptisch. Villeneuve war ein Rookie, ohne Formel-1-Meriten. Doch Enzo glaubte an ihn – instinktiv. Und er sollte Recht behalten.

Leidenschaft auf Rädern

Villeneuve fuhr nicht, um zu gewinnen – er fuhr, um zu überleben, zu bestehen, zu kämpfen. Jeder Einsatz war eine Demonstration von Willenskraft. Selbst mit beschädigtem Auto, ohne Reifen oder bei strömendem Regen – Gilles gab nie auf. Seine Duelle, besonders jenes mit René Arnoux beim GP von Frankreich 1979 in Dijon, gelten als das intensivste Zweikampf-Spektakel der Formel-1-Geschichte. Runde um Runde Rad an Rad – ohne Rücksicht, aber mit Respekt.

Ferrari nannte ihn später „einen Ritter alter Schule“, jemand, der mit Ehre kämpfte, nie taktierte, nie spielte. Gilles Villeneuve war ein Fahrer, der für Ferrari starb, bevor er alt wurde.

Der tödliche Mythos

Am 8. Mai 1982 geschah das Unfassbare: Im Qualifying zum Großen Preis von Belgien in Zolder verunglückte Villeneuve tödlich. Er wollte unbedingt die Zeit seines Teamkollegen Didier Pironi unterbieten – eine Reaktion auf einen als Verrat empfundenen Überholvorgang im vorherigen Rennen in Imola.

Villeneuve raste mit über 250 km/h auf Jochen Mass auf, der gerade langsamer wurde. Gilles' Ferrari hob ab, zerbarst – der Kanadier wurde aus dem Wagen geschleudert, starb wenig später an seinen Verletzungen. Die Formel 1 verlor einen ihrer mutigsten Söhne – und Ferrari verlor seinen Herzensfahrer.

Enzo Ferrari sprach später selten über diesen Tag. Doch in einem seiner letzten Interviews sagte er:

„Gilles war für mich mehr als ein Fahrer. Er war mein Sohn auf der Strecke. Niemand hat Ferrari je so geliebt wie er.“

Ein Mythos, der bleibt

Heute trägt die Rennstrecke in Montreal seinen Namen: Circuit Gilles Villeneuve. Seine Statue steht in Fiorano. In Maranello hängt sein Helm im Museum – ein stilles Denkmal.

Villeneuve gewann nie einen Weltmeistertitel. Doch er gewann die Herzen. Für Enzo Ferrari und viele Tifosi war er der wahre Champion – weil er nie kalkulierte, nie aufgab, nie nachließ. Und weil er zeigte, dass ein Ferrari nicht nur schnell, sondern auch würdevoll sein kann.

8.3 – Die Ära Jean Todt, Schumacher und Dominanz (1996–2004)

Nach Jahrzehnten voller Glanz, Rückschläge und ewiger Hoffnung begann Mitte der 1990er-Jahre die wohl strategisch klügste und sportlich erfolgreichste Phase der Scuderia Ferrari – die Ära von Jean Todt, Michael Schumacher, Ross Brawn und Rory Byrne. Sie war nicht nur durch Titel geprägt, sondern durch eine beispiellose kulturelle Wandlung: Ferrari wurde von einem stolzen, oft chaotischen Mythos zu einer präzise getakteten Erfolgsmachine.

Jean Todt – Der stille Architekt

Der Franzose Jean Todt wurde 1993 Teamchef von Ferrari – ein Bruch mit Tradition, denn Ferrari war bis dahin immer von Italienern geführt worden. Doch Enzo Ferrari war nicht mehr da, und Luca di Montezemolo wollte Wandel. Todt war kein Mann großer Worte, aber ein taktischer Stratege. Er wusste: Ferrari braucht Struktur, nicht Emotion.

Er begann, die Scuderia von Grund auf umzubauen – langsame Entscheidungswege wurden verkürzt, Verantwortlichkeiten klar definiert, technische Entwicklungsprozesse modernisiert. Doch Todt wusste auch: Ein starkes Team braucht einen starken Fahrer.

Michael Schumacher – Der entscheidende Puzzlestein

1996 holte Ferrari Michael Schumacher, damals bereits zweifacher Weltmeister mit Benetton. Viele hielten das für einen riskanten Schritt – Ferrari hatte seit 1979 keinen Fahrer-WM-Titel mehr gewonnen, der letzte Konstrukteurstitel lag über ein Jahrzehnt zurück. Doch Schumacher sah die Herausforderung – und das Potenzial.

Mit ihm kamen zwei weitere Schlüsselpersonen: Chefstratege Ross Brawn und Chefdesigner Rory Byrne. Gemeinsam mit Todt bildeten sie das sogenannte „Dream Team“ – ein harmonisches, zielgerichtetes Quartett, das alle Aspekte eines Formel-1-Teams abdeckte: Führung, Technik, Taktik, Fahrer.

Die Jahre des Aufbaus (1996–1999)

Die ersten Jahre waren schwierig: 1996 war ein Lehrjahr, 1997 endete dramatisch mit Schumachers Disqualifikation im Titelduell mit Villeneuve. 1998 wurde man knapp von McLaren-Mercedes geschlagen, 1999 stoppte ein Beinbruch Schumachers Titeljagd.

Doch das Team lernte. Jedes Jahr wurde der Wagen besser, die Boxenstopps schneller, die Strategie präziser. Ferrari entwickelte sich von einem leidenschaftlichen Herausforderer zu einer disziplinierten Siegmaschine.

Die Dominanz beginnt – 2000 bis 2004

2000 war es endlich soweit: Michael Schumacher holte den Fahrer-WM-Titel – der erste für Ferrari seit Jody Scheckter 1979. Es war mehr als ein sportlicher Erfolg – es war eine emotionale Erlösung.

Es folgten fünf Jahre, die als Dynastie in die Formel-1-Geschichte eingingen:

2000–2004: Fünf Fahrer- und Konstrukteurstitel in Serie

15 Siege in einer Saison (2002)

13 Siege durch Schumacher allein (2004)

Ferrari war in dieser Zeit unangreifbar. Die Kombination aus Schumachers Präzision, Brawns Strategie, Byrnes Konstruktion und Todts Führung war beispiellos. Das Team funktionierte wie ein Uhrwerk – und das über Jahre hinweg.

Warum es funktionierte

Der Erfolg basierte nicht auf Einzelpersonen, sondern auf Struktur und Vertrauen. Todt ließ arbeiten, statt zu inszenieren. Brawn plante Rennen mit militärischer Exaktheit. Byrne baute Autos, die robust, schnell und fahrerfreundlich waren. Und Schumacher? Er testete, trainierte, motivierte – und lieferte.

Ferrari wurde von einem emotionsgetriebenen Mythos zu einem professionell geführten Werksteam, ohne seine Seele zu verlieren. Und genau darin lag die Einzigartigkeit dieser Ära: Präzision ohne Kälte. Leidenschaft ohne Chaos.

Eine Ära für die Ewigkeit

Die Jahre 1996 bis 2004 schrieben Ferrari in die moderne Formel-1-Geschichte ein wie nie zuvor. Es war die Zeit, in der Maranello nicht nur erinnerte, sondern dominierte. Die Scuderia war nicht mehr nur Mythos – sie war Maßstab.

Für viele Fans bleibt diese Ära bis heute das goldene Zeitalter Ferraris. Und es zeigt: Mit der richtigen Kombination aus Menschen, Strategie und Disziplin kann selbst ein Mythos neugeboren werden.

8.4 Ferrari gegen Mercedes & Red Bull – Neue Herausforderungen

Nach der goldenen Ära unter Michael Schumacher und dem Konstrukteurstitel 2008 begann für Ferrari eine neue Phase – eine Ära des Suchens. Während der Mythos ungebrochen blieb, veränderte sich die Formel 1 rasant. Neue Regeln, Hybridsysteme, technische Megaprojekte und datenbasierte Strategien begünstigten andere Teams. Ferrari war plötzlich nicht mehr Taktgeber – sondern Jäger.

Die Hybrid-Ära beginnt – Mercedes zieht davon

Mit dem Beginn der Hybrid-Ära 2014 begann eine Phase, in der Mercedes-AMG Petronas den Sport dominierte. Das Team um Lewis Hamilton, Toto Wolff und ein hochentwickeltes Power-Unit-Konzept gewann acht Konstrukteurstitel in Folge – von 2014 bis 2021. Ferrari versuchte mitzuhalten, doch die technologische Kluft war tief. Besonders in den Jahren 2014 bis 2016 mangelte es an Motorleistung, Effizienz und Standfestigkeit.

Sebastian Vettel, der 2015 zu Ferrari wechselte, versprach zunächst eine Rückkehr zu altem Glanz. Doch trotz einzelner Siege und vielversprechender Zwischenphasen fehlte es dem Team an Konstanz, Strategie und Weiterentwicklung. Besonders 2017 und 2018 sah es kurzzeitig nach einem Titelkampf gegen Mercedes aus – doch Fehler auf und neben der Strecke kosteten Ferrari beide Jahre entscheidend wichtige Punkte.

Red Bull – jung, schnell, gnadenlos präzise

Parallel entwickelte sich Red Bull Racing von einem Außenseiter zum technologischen Giganten. Mit einem Fokus auf Aerodynamik, einer perfekten Verbindung zu Adrian Newey und dem jungen Ausnahmetalent Max Verstappen gelang dem Team spätestens ab 2021 der Durchbruch. Verstappen wurde nicht nur Weltmeister – er dominierte. Seine Aggressivität, gepaart mit einem überlegenen Chassis-Konzept, brachte Ferrari erneut in die Zuschauerrolle.

Ferrari fehlte es in dieser Phase vor allem an Entscheidungsstärke und Stabilität. Strategiefehler, Boxenpannen und inkonsistente Upgrades prägten die Jahre 2019 bis 2022. Das Auto war meist schnell – aber nie vollständig konkurrenzfähig über eine ganze Saison.

Der Druck des Mythos

Ferraris größte Herausforderung war – und ist – der eigene Anspruch. Während andere Teams wie Mercedes und Red Bull ruhig und systematisch arbeiteten, war in Maranello jeder Misserfolg ein nationales Ereignis. Die Presse, die Tifosi, die Führungsetage – sie alle erwarteten mehr als Podien. Sie erwarteten Ruhm.

Doch moderner Motorsport verlangt langfristige Strategien, Kontinuität und eine Fehlerkultur, die intern bleibt. Ferrari dagegen reagierte oft impulsiv: Teamchefs wurden gewechselt, Konzepte über Bord geworfen, Fahrer geopfert. Dieses Unruhestiften kostete wertvolle Zeit – und Vertrauen.

2023 und darüber hinaus – Hoffnung auf Stabilität

Mit der Verpflichtung von Frédéric Vasseur als Teamchef und der Fahrerpaarung Charles Leclerc & Carlos Sainz richtete sich Ferrari ab 2023 neu aus. Der SF-23 war ein schnelles Auto – aber erneut nicht konstant genug. Dennoch: Es zeichnete sich ab, dass Ferrari lernte, moderner zu denken.

Der Abstand zur Spitze blieb zwar spürbar, doch das Team begann, sich intern zu stabilisieren. Windkanalzeiten wurden optimiert, Strategieeinheiten neu strukturiert, technisches Personal verstärkt. Man arbeitete an der Rückkehr zur Form – Schritt für Schritt, statt Sprung um Sprung.

Eine Marke kämpft – nicht nur auf der Strecke

Ferrari ist und bleibt das emotionalste Team der Formel 1. Doch gegen die Ingenieursgewalt von Mercedes und die Rennintelligenz von Red Bull reicht Mythos allein nicht. Ferrari steht vor der Herausforderung, Tradition mit Präzision zu vereinen – und den Spagat zwischen Stolz und Fortschritt zu meistern.

Ob es gelingt? Die Geschichte zeigt: Wer Ferrari abschreibt, irrt sich oft. Und wer an sie glaubt, weiß: Jeder rote Sieg ist mehr als ein Triumph – er ist ein Kapitel für die Ewigkeit.

8.5 – Die Zukunft der Scuderia – Strategie, Wandel, Hoffnung

Ferrari ist mehr als ein Rennteam – es ist eine emotionale Instanz, ein nationales Symbol, ein globaler Mythos. Doch in den letzten Jahren hat die Formel 1 sich weiterentwickelt: Die Zeiten, in denen Emotion und Intuition allein ausreichten, sind vorbei. Daten, Simulationen, Prozesse und langfristige Strategien entscheiden heute über Siege. Wer mithalten will, braucht nicht nur PS – sondern Präzision.

Ferrari steht damit vor einer der größten Herausforderungen seiner Geschichte: Wie kann man die eigene Seele bewahren – und dennoch technisch modernisieren?

Neustart unter Frédéric Vasseur

Mit der Ernennung des Franzosen Frédéric Vasseur zum Teamchef im Jahr 2023 beginnt eine neue Phase in Maranello. Vasseur bringt die seltene Mischung aus Motorsportleidenschaft, Managementerfahrung und strategischer Kühle mit. Anders als seine Vorgänger – die oft zwischen Tifosi-Druck und interner Politik zerrieben wurden – scheint er bereit, langfristig zu denken.

Sein Credo: Stabilität vor Aktionismus. Vasseur will Strukturen verbessern, nicht Köpfe rollen lassen. Technikchef Enrico Cardile und Motorenleiter Enrico Gualtieri erhalten klarere Verantwortungsbereiche, die Kommunikation zwischen Werk und Rennstrecke wurde neu definiert. Ziel ist es, Ferrari zu einem geschlossenen System zu machen – wie es Mercedes und Red Bull längst sind.

Fahrer-Duo mit Zukunft

Mit Charles Leclerc und Carlos Sainz verfügt Ferrari über eines der stärksten und ausgewogensten Fahrerteams der Gegenwart. Leclerc gilt als emotionaler Fanliebling mit unglaublichem Talent, Sainz als analytischer, konstanter Punktesammler. Beide Fahrer identifizieren sich stark mit Ferrari – ein seltener Glücksfall.

Doch Ferrari weiß: Talent allein reicht nicht. Es braucht ein Auto, das über eine ganze Saison funktioniert – auf jeder Strecke, bei jedem Wetter, in jedem Rennformat. Genau daran arbeitet das Team mit Hochdruck.

Technik und Infrastruktur im Umbruch

Ferrari investiert massiv in neue Testsysteme, Simulationsplattformen und Windkanalanlagen. In der modernen Formel 1 entscheiden Millimeter und Mikrosekunden – wer vorne mitfahren will, muss auf allen Ebenen exzellent sein.

Gleichzeitig steht der Formel-1-Zirkus selbst vor großen Veränderungen:

Ab 2026 kommen neue Motorenregeln mit Fokus auf elektrische Effizienz.

Nachhaltigkeit, synthetische Kraftstoffe und CO₂-Neutralität werden Pflicht.

Neue Rennformate und wirtschaftliche Rahmenbedingungen verändern das Spiel.

Ferrari bereitet sich darauf vor – mit dem Ziel, nicht nur mitzuspielen, sondern zu führen.

Der Mythos als Verpflichtung

Was Ferrari von anderen Teams unterscheidet, ist der ständige Druck der eigenen Geschichte. Jedes Rennen ist eine Erinnerung an Enzo. Jeder neue Wagen trägt mehr als nur ein Emblem – er trägt ein Versprechen.

Der Mythos Ferrari ist kein Polster. Er ist eine Verpflichtung. Und genau darin liegt die Chance: Wenn Technik, Struktur und Emotion in Einklang kommen, kann Ferrari wieder das werden, was es einmal war – die ultimative Referenz.

Hoffnung, nicht Erwartung

Die Zukunft Ferraris liegt nicht in einem Fahrer oder einem Rennwagen – sondern im System, das dahintersteht. Strategie, Planung, Geduld. Das neue Ferrari denkt langfristig – und das ist gut so.

Denn wenn Ferrari eines kann, dann ist es zurückkehren. Immer wieder. Und wenn der Tag kommt, an dem ein roter Wagen wieder ganz oben steht – dann wird es sich nicht nur wie ein Sieg anfühlen. Es wird sich anfühlen wie Heimkehr.

Kapitel 9: Nach dem Commendatore – Krise, Wandel und neue Helden

Der Tod Enzo Ferraris im August 1988 markierte das Ende einer Ära – nicht nur emotional, sondern strukturell. Der Mann, der sein Unternehmen über fast sechs Jahrzehnte geprägt hatte, war nicht mehr da. Was blieb, war eine globale Ikone ohne ihren Architekten. Und genau darin lag die Herausforderung: Ferrari musste lernen, Ferrari zu sein – ohne Ferrari.

Die ersten Jahre nach dem Commendatore waren geprägt von Suche und Unsicherheit. Die Fiat-Gruppe, die bereits seit 1969 Anteile hielt, übernahm mehr Verantwortung. Doch das Unternehmen wirkte wie ein Erbe, das man ehrte, aber nicht vollständig verstand. Die Formel-1-Ergebnisse schwankten, die Modellpolitik war inkonsequent, und die Seele des Unternehmens schien zu flackern.

Erst mit der Ernennung von Luca di Montezemolo zum Präsidenten 1991 begann ein echter Wandel. Montezemolo, einst persönlicher Assistent Enzos, kannte den Geist des Hauses – und zugleich die Notwendigkeit zur Modernisierung. Unter seiner Führung wurde Ferrari neu aufgestellt: Luxusmarke, Rennteam, Hightech-Schmiede. Marketing, Design, Produktion – alles wurde vernetzt, verfeinert, strategisch orchestriert.

Parallel dazu wuchsen neue Helden heran. Jean Todt, Michael Schumacher, Ross Brawn – sie formten eine Scuderia, die wieder lernte zu dominieren. Nicht mehr aus dem Bauch heraus, sondern mit System. Doch auch auf der Straße entwickelte sich Ferrari weiter: Der F355, der Enzo, später der LaFerrari – sie zeigten, dass der Mythos nicht nur weiterlebte, sondern neu geboren wurde.

Nach dem Commendatore wandelte sich Ferrari – von der Werkstatt eines Genies zum Weltunternehmen mit Seele. Es war ein riskanter Balanceakt. Doch am Ende gelang etwas, das kaum einer für möglich hielt: Die Legende Ferrari überlebte ihren Schöpfer.

9.1 – Post-Enzo: Die Ferrari-Führung unter Fiat

Mit dem Tod Enzo Ferraris am 14. August 1988 endete nicht nur eine Ära – es begann ein Kapitel voller Fragen. Ferrari stand ohne seinen Gründer da, ohne seine moralische Autorität, ohne das verkörperte Gedächtnis der Marke. Und obwohl der Mythos lebte, fehlte das Zentrum, das ihn zusammenhielt. Wer sollte Ferrari nun führen? Wer konnte entscheiden, was ein „echter“ Ferrari war – ohne Enzos Stimme?

Die Antwort lag in einer Struktur, die längst vorbereitet war: Fiat.

Ein Erbe mit Vorlauf: Fiat als Anteilseigner

Bereits 1969 hatte Enzo Ferrari 50 % seiner Firma an die Fiat-Gruppe verkauft – nicht aus Begeisterung, sondern aus Notwendigkeit. Ferrari war finanziell unter Druck, wollte aber unabhängig im Motorsport bleiben. Der Deal mit Fiat garantierte Kapital und Ressourcen, ließ Enzo aber die Kontrolle über die Rennabteilung und die Fahrzeugphilosophie behalten.

1974 erhöhte Fiat seinen Anteil auf 90 %. Enzo hielt nur noch symbolische 10 %, blieb aber bis zu seinem Tod die Leitfigur. Es war eine klare Arbeitsteilung: Fiat kümmerte sich um Produktion, Vertrieb und Industrie – Enzo um Seele, Strategie und Motorsport.

Nach Enzos Tod übernahm Fiat formal die Führung – doch was folgte, war kein entschlossener Aufbruch, sondern eine Phase der Orientierungslosigkeit.

Die frühen 1990er: Führung ohne Richtung

Zwischen 1989 und 1991 wurde Ferrari von einer Reihe von Fiat-Managerfiguren geführt, die das Unternehmen als Luxusmarke mit Potenzial, aber ohne klare Linie betrachteten. Die Rennabteilung verlor an Effizienz, die Straßenfahrzeuge litten unter Qualitätsproblemen, und die Markenidentität verwässerte.

Intern war spürbar: Fiat verstand die Magie, aber nicht die Mechanik dahinter. Die Bürokratie nahm zu, Entscheidungswege wurden länger, technisches Personal demotiviert. Ferrari drohte, zu einer Abteilung in einem Industriekonzern zu werden – statt zu einem pulsierenden Mythos.

Auch das Motorsport-Team litt. Zwischen 1989 und 1993 wechselten Fahrer, Techniker und Teamchefs fast im Jahresrhythmus. Trotz Einzelerfolgen (wie 1989 in Brasilien oder 1990 mit Prost in Imola) fehlte die Konstanz – und der strategische Plan.

Die Rückkehr der Identität: Montezemolo übernimmt

Der Wendepunkt kam 1991, als Luca Cordero di Montezemolo zum Präsidenten von Ferrari berufen wurde. Ein Mann, der nicht nur Manager, sondern auch Vertrauter Enzos gewesen war. Als junger Teamchef der Scuderia hatte er 1975 mit Niki Lauda den Titel gewonnen – und wusste, was Ferrari bedeutete.

Montezemolo war charismatisch, strategisch und tief mit der Marke verbunden. Er verstand es, zwischen Fiat-Strukturen und Ferrari-Kultur zu vermitteln – und entwickelte einen Plan, der Ferrari neu positionierte, ohne seine Seele zu verlieren.

Ferrari wird Premium – und bleibt Mythos

Montezemolos Philosophie war klar: Ferrari sollte kein reiner Autobauer sein, sondern ein Kulturobjekt. Jedes Modell musste ein Statement sein – handwerklich, technologisch, emotional. Die Produktion wurde verschlankt, Qualitätsstandards erhöht, das Design fokussiert.

Unter seiner Führung entstanden Ikonen wie:

F355 (1994) – der erste „neue Ferrari“ mit Alltagstauglichkeit und Supersportler-DNA

360 Modena (1999) – ein Design- und Technikmeilenstein

Enzo Ferrari (2002) – das Hypercar als Hommage an den Gründer

Gleichzeitig wurde die Marke systematisch gepflegt: Ferrari-Stores wurden eröffnet, die Museumspräsenz ausgebaut, Merchandising professionalisiert. Ferrari wurde zur emotionalen Luxusmarke mit globaler Strahlkraft.

Die Formel 1 wird zur Chefsache

Parallel zum Straßenwagengeschäft reformierte Montezemolo die Scuderia. Er holte 1993 Jean Todt, später Michael Schumacher, Ross Brawn und Rory Byrne – und schuf das erfolgreichste Team der Formel-1-Geschichte (siehe Kapitel 8.3).

Was viele nicht wissen: Fiat überließ Ferrari in dieser Phase weitgehend freie Hand. Montezemolo genoss das Vertrauen der Konzernführung – nicht nur wegen seiner Vergangenheit, sondern wegen seiner Ergebnisse. Ferrari wurde zwar geführt, aber nicht gegängelt. Diese Autonomie war zentral für die sportliche und wirtschaftliche Wiedergeburt der Marke.

Ferrari unter Fiat – eine symbiotische Beziehung

Trotz aller Kritik an der Bürokratie der 1990er war die Beziehung zwischen Ferrari und Fiat nie rein instrumentell. Fiat profitierte von der Strahlkraft Ferraris – und Ferrari nutzte Fiats Ressourcen. Es war eine gegenseitige Abhängigkeit, die funktionierte, solange Ferrari seine kulturelle Identität bewahren konnte.

Im Unterschied zu anderen Konzernen (etwa Daimler mit AMG oder VW mit Bugatti) ließ Fiat der Marke ihren Mythos. Und genau das war ihr größter Trumpf.

Die Führung ohne Ferrari – aber mit Ferrari im Herzen

Nach Enzo Ferraris Tod stand das Unternehmen an einem Scheideweg. Fiat übernahm – aber erst mit der Rückkehr von Vertrauten wie Montezemolo fand Ferrari zurück zu sich selbst. Die Fiat-Führung war nicht visionär, aber ermöglichend. Und das genügte – weil die richtigen Menschen an den richtigen Stellen wirkten.

So wurde aus der Krise eine Chance. Aus dem Mythos ein Managementfall. Und aus der Vergangenheit ein Fundament, auf dem Ferrari zur modernsten Traditionsmarke der Welt werden konnte.

9.2 – Die Ära Montezemolo – Eleganz, Image und Business

Als Luca Cordero di Montezemolo 1991 die Führung bei Ferrari übernahm, befand sich das Unternehmen in einer Übergangsphase. Die Ära Enzo war vorbei, die 80er-Jahre waren geprägt von Unsicherheit, und die Marke Ferrari hatte trotz unverändertem Glanz an Substanz verloren. Montezemolo war entschlossen, das zu ändern – und zwar nicht nur auf der Rennstrecke, sondern im gesamten Markenverständnis.

Sein Ziel war klar: Ferrari sollte nicht nur die schnellste, sondern auch die eleganteste, begehrenswerteste und wirtschaftlich erfolgreichste Automarke der Welt werden. Und dabei sollte die Identität Ferraris nicht verwässert, sondern neu definiert werden – auf Höhe der Zeit.

Der Anfang: Aufräumen und Neuausrichten

Montezemolo war kein Unbekannter. Er hatte bereits Mitte der 1970er als Teammanager mit Niki Lauda den WM-Titel geholt und galt als talentierter Kommunikator und Stratege. Sein erster Schritt war die Neuordnung der Strukturen: klare Hierarchien, modernisierte Produktionsprozesse, ein neues Qualitätsmanagement. Das Ziel: Jeder Ferrari musste nicht nur besonders, sondern auch perfekt sein.

Intern führte er eine Philosophie ein, die Enzo Ferrari wohl gefallen hätte: kompromisslose Leidenschaft, aber mit unternehmerischer Weitsicht.

Straßenfahrzeuge – Ikonen mit Charakter

Unter Montezemolos Führung wurde das Produktportfolio komplett überarbeitet. Modelle wie der 348 galten als technisch veraltet – es musste etwas Neues her, ohne die Seele der Marke zu verlieren.

Sein erster Meilenstein: der Ferrari F355 (1994) – ein moderner Sportwagen mit V8-Motor, brillanter Fahrbarkeit, ikonischem Design und erstmals einem sequentiellen F1-Getriebe. Der F355 wurde zum Symbol des neuen Ferrari: schnell, elegant, fahrbar.

Es folgten:

Ferrari 360 Modena (1999): Leichtbau, Aluminium-Chassis, pure Linien

Ferrari Enzo (2002): Hommage an den Gründer, Technikträger mit F1-DNA

F430, 612 Scaglietti, 599 GTB Fiorano: Fahrzeuge, die Ferrari in der Oberklasse verankerten

Montezemolo bestand darauf, dass jeder neue Ferrari sowohl auf der Straße als auch auf der Rennstrecke bestehen musste – in Technik, Sound, Design und Emotion.

Design als Differenzierungsmerkmal

Ferraris Designlinie wurde unter Montezemolo geprägt von klaren, fließenden Formen, die das Auto nicht nur schnell, sondern auch edel wirken ließen. Die Partnerschaft mit Pininfarina wurde intensiviert, gleichzeitig aber mit neuen Impulsen versehen.

Dabei stand stets im Zentrum: Eleganz ohne Kompromiss. Ein Ferrari musste auffallen – nicht durch Effekthascherei, sondern durch zeitlose Ästhetik.

Das Resultat war eine Serie von Fahrzeugen, die nicht nur verkauft wurden, sondern gesammelt, bewundert und ausgestellt.

Ferrari als Marke – Luxus jenseits des Autos

Montezemolo verstand als einer der ersten Manager in der Autobranche, dass eine Marke wie Ferrari nicht auf das Produkt beschränkt ist. Er baute Ferrari zu einem Erlebnis-Universum aus:

Ferrari Flagship-Stores weltweit

Ferrari World Abu Dhabi – ein Themenpark als Markentempel

Lizenzpartnerschaften für Uhren, Bekleidung, Accessoires

Ferrari-Museen in Maranello und Modena

Exklusive Fahrveranstaltungen und Trackdays für Kunden

Diese Strategie war nicht Selbstzweck. Sie diente dazu, Ferrari als Lifestyle-Statement zu etablieren – mit wirtschaftlichem Erfolg. Die Margen stiegen, die Wartezeiten für Fahrzeuge wurden länger, der Wiederverkaufswert stabilisierte sich auf Rekordniveau.

Formel 1 – Erfolg als Markenmotor

Parallel zur wirtschaftlichen Renaissance sorgte Montezemolo auch auf der Rennstrecke für eine neue Ära. Mit dem Aufbau des Dream Teams um Jean Todt, Michael Schumacher, Ross Brawn und Rory Byrne (siehe Kapitel 8.3) gelang ab 2000 die spektakulärste Erfolgsserie der Ferrari-Geschichte.

Doch Montezemolo war nicht nur Förderer, sondern Schirmherr. Er hielt politischen Druck von der Scuderia fern, schützte seine Leute, sorgte für Ressourcen – und machte klar: Ferrari muss auch sportlich führen, um als Marke zu glänzen.

Internationalisierung und Kontrolle

Ein weiterer Eckpfeiler seiner Strategie war die Internationalisierung der Marke, ohne ihre italienische Seele zu verlieren. Ferrari wurde unter seiner Führung weltweit synchronisiert, aber nie gleichgeschaltet. In den USA, China, dem Nahen Osten – überall wuchs der Absatz, begleitet von exklusiven Veranstaltungen, personalisierten Kundenerlebnissen und regionaler Anpassung bei gleichzeitiger Markenhomogenität.

Dabei blieb Montezemolo stets der Kulturwächter. Kein Modell, kein Logo, keine Kooperation wurde ohne sein finales Okay umgesetzt. Er hielt an der Idee fest, dass Ferrari nicht jedem gehören darf – sondern nur denen, die es sich verdienen.

Der Mann, der Ferrari wieder groß machte

Luca di Montezemolo war mehr als ein Geschäftsführer – er war ein Kurator des Mythos. Er verband wirtschaftliche Schärfe mit kulturellem Feingefühl, Innovation mit Tradition. Unter seiner Leitung wurde Ferrari nicht nur sportlich und wirtschaftlich erfolgreich – sondern zu einer globalen Luxusmarke mit Seele.

Die Ära Montezemolo zeigt: Ferrari kann auch ohne Enzo Ferrari wachsen – solange die richtigen Menschen im Geiste des Commendatore handeln.

9.3 – Die Technikrevolution der 2000er – Carbon, Windkanal, Elektronik

Während die 1980er- und 1990er-Jahre für Ferrari von strukturellem Wandel, Markenbildung und sportlicher Rückkehr geprägt waren, läuteten die 2000er-Jahre eine tiefgreifende technologische Revolution ein. Es war das Jahrzehnt, in dem sich der Traditionshersteller endgültig vom handwerklichen Manufakturdenken zur Hightech-Schmiede mit Formel-1-Genen verwandelte.

Ferrari wurde zum Symbol für automobile Spitzenforschung – auf der Straße wie auf der Rennstrecke. Der Fokus lag dabei auf drei Schlüsselbereichen: Carbonfaser-Leichtbau, aerodynamische Entwicklung im Windkanal und digitale Elektroniksysteme, die eine neue Ära des Fahrens einleiteten.

1. Carbon – Vom Flugzeugwerkstoff zur Ferrari-DNA

Carbonfaser – einst eine Exotenlösung aus der Luftfahrt – wurde in den 2000er-Jahren zum zentralen Baustoff bei Ferrari. Der Grund war klar: Kein anderes Material bietet bei so geringem Gewicht eine derart hohe Steifigkeit. Und genau das war entscheidend – sowohl für Supersportwagen als auch für Formel-1-Boliden.

Bereits im Ferrari F50 (1995) kamen erste Carbonkomponenten zum Einsatz. Doch der wirkliche Durchbruch erfolgte mit dem Ferrari Enzo (2002), dessen Monocoque und Karosserieteile fast vollständig aus Kohlefaser bestanden. Der Enzo war nicht nur eine Hommage an den Firmengründer – er war ein fahrbares Technologiedemonstrationsobjekt.

Die Vorteile lagen auf der Hand:

Verbesserte Crashsicherheit trotz Gewichtsersparnis

Erhöhte Torsionssteifigkeit für präziseres Fahrverhalten

Leichterer Aufbau für bessere Leistungsgewichte

Diese Fortschritte beeinflussten auch spätere Serienmodelle wie den 430 Scuderia oder den 599 GTO, in denen Carbon zunehmend in Fahrwerkskomponenten, Interieurteilen und sogar Bremsen (Carbon-Keramik) Einzug hielt.

2. Aerodynamik – Der Windkanal wird zur Waffe

Ein weiterer Meilenstein der 2000er war die massive Investition in aerodynamische Forschung. Ferrari war einer der ersten Hersteller, der einen eigenen Windkanal ausschließlich für Straßenfahrzeuge errichtete – ein klares Zeichen für die Verschmelzung von Rennsport und Serienentwicklung.

Der 1997 in Betrieb genommene Windkanal in Maranello wurde zum Herzstück der Entwicklungsabteilung. Hier testete man:

Luftstromverläufe über Karosserie und Unterboden

Kühlungseffizienz und Luftwiderstand

Auftrieb und Anpressdruck für Hochgeschwindigkeitsstabilität

Geräuschoptimierung bei hohen Geschwindigkeiten

Besonders bei Modellen wie dem 430 Scuderia, dem 458 Italia und später dem F12berlinetta wurde die Aerodynamik nicht nur funktional, sondern visuell erlebbar – etwa durch integrierte Luftkanäle, aktive Spoiler oder den Verzicht auf klassische Flügel.

Im Rennsport führte diese Entwicklung zu immer radikaleren Formen: Schlanke Cockpits, komplexe Diffusoren, mit CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) unterstützte Entwicklungen. Der Windkanal wurde zum entscheidenden Werkzeug in der Performance-Formel.

3. Elektronik – Kontrolle trifft Intelligenz

Der wohl tiefgreifendste Wandel jedoch betraf die Elektronik. Wo früher Mechanik herrschte, zogen nun Mikroprozessoren, Sensoren und Softwarealgorithmen ein – auf Straße wie Strecke. Die Elektronik war nicht mehr nur Assistenz, sondern strategischer Faktor.

Ferrari führte in den 2000er-Jahren bahnbrechende Systeme ein, darunter:

E-Diff (elektronisch geregeltes Differenzial): verbesserte Traktion bei Kurvenausgang

F1-Trac: Traktionskontrolle mit Lernalgorithmus

Manettino-Schalter am Lenkrad: direkt aus der Formel 1 übernommen, ermöglichte dem Fahrer, Fahrdynamiksysteme wie ESP, Dämpfung und Gasannahme in Echtzeit anzupassen

Magnetorheologische Dämpfer: adaptives Fahrwerk mit blitzschneller Reaktion auf Straßenverhältnisse

Diese Technologien machten Ferrari-Fahrzeuge schneller, sicherer und kontrollierbarer – ohne dabei das emotionale Fahrerlebnis zu verwässern. Im Gegenteil: Durch intelligente Systeme wurde der Fahrer aktiv unterstützt, nicht ersetzt.

Im Motorsport wurde Elektronik zum unsichtbaren Rennleiter: Telemetrie, Live-Datenüberwachung, Strategiesoftware – alles arbeitete im Hintergrund, um hundertstel Sekunden herauszuholen.

Die Verschmelzung von Straße und Rennstrecke

Die 2000er-Jahre markierten die Phase, in der Ferrari die Formel 1 nicht mehr nur als Imagekanal nutzte, sondern als Entwicklungslabor. Viele der Technologien, die auf der Strecke erprobt wurden, flossen zeitnah in die Serienproduktion.

Beispiele:

Das F1-Getriebe aus dem 355 Challenge wurde zum Serienstandard

Carbon-Keramik-Bremsen aus der F1 fanden ihren Weg in den Enzo

Aerodynamik-Elemente, wie der „S-Duct“ aus der F1, wurden beim 488 Pista übernommen

Hybridtechnologie (KERS) aus der F1 inspirierte später den LaFerrari

Ferrari wurde zum Inbegriff der symbiotischen Beziehung zwischen Motorsport und Straßenauto. Kein anderer Hersteller verband beide Welten so nahtlos – und mit solcher Konsequenz.

Der Technologiewechsel als Identitätsverstärker

Die Technikrevolution der 2000er war keine Abkehr vom Mythos – sie war seine logische Fortsetzung. Ferrari erkannte früh, dass die Zukunft nicht in Nostalgie, sondern in Innovation liegt. Doch anders als andere Marken vergaß Ferrari dabei nie, woher es kam.

Carbon machte die Fahrzeuge leichter, der Windkanal schneller, die Elektronik klüger – aber das Herz schlug weiter analog. Der Sound, das Design, das Gefühl – sie blieben unverwechselbar.

Ferrari bewies, dass man technologisch führend und emotional unverwechselbar sein kann. Und das macht die Marke bis heute einzigartig.

9.4 – Hybride Supercars und der Spagat zwischen Tradition und Zukunft

Ferrari – das steht für röhrende V12-Motoren, mechanische Präzision und die pure Essenz automobiler Emotion. Jahrzehntelang war klar: Ein echter Ferrari hat einen Verbrennungsmotor im Herzen, idealerweise zwölf Zylinder, hohe Drehzahlen, charakteristischen Sound – und keine Kompromisse. Doch mit dem 21. Jahrhundert veränderten sich die Spielregeln.

Klimawandel, Emissionsgesetze, neue Kundenerwartungen und technologische Revolutionen setzten auch Ferrari unter Druck. Die Antwort des Traditionsherstellers war typisch für Maranello: nicht Anpassung durch Verzicht, sondern durch Vision. Und so begann Ferrari, an etwas zu arbeiten, das lange undenkbar schien: Hybridantrieb – nicht als Notlösung, sondern als Leistungsversprechen.

Der erste Schritt: KERS und die Formel 1